|  |

|  |

Krishna and Vasanta - Harsha V Dahejia, Canada e-mail: harshadehejia@hotmail.com Images courtesy: Harsha V Dehejia May 10, 2010 The seasons for us have a living presence embodying the mysterious essence of growth and decay and regrowth, tied to the movements of the cosmos and the rhythms of the earth, touching the deepest longings and aspirations, moods and feelings of humans, providing a scenario upon which we celebrate and understand life and love. Of all the human emotions, that of romantic love is closely tied to the changing seasons, each month bringing a special message to the beloved, every season a special reminder of the joys of love and longing, the changing seasons reflecting the varying moods of romantic love and the songs of the seasons echoing a melody that resonates through the heart of the lover and the beloved.   The shringara rasa of Krishna is best epitomised by the colours and sounds, the textures and the aromas, the mood and the ethos of Vasanta or spring. Vasanta is raja ritu, the king of seasons. It is in Vasanta that nature comes to life, mango blossoms appear, colours deepen, the birds and the bees are joyous, love awakens and erotic feelings quicken, the mind is energised and the heart throbs with excitement. Nature's fecundity and luxuriance is matched only by the heart throbbing anticipation, amorous desires, tremulous coyness and expectant longing of the romantic nayika. In the various colours of the fecundity of Vasanta, there is nature's romance, there is an agamana or a welcome, in its radiance there is an invitation, in its unspoken words there is a song of love, in its movements there is the dance of amour, and in its quivering there is the tremulous desire of love. Nature in Vasanta is like a bride adorned in red like the Kinshuka flower, raktanshuka navavadhuhu eva, in the words of Kalidasa (Ritusamhara 6.19). Kalidasa goes on to describe spring with these words:

To be adorned is to invite and to welcome, to be bejeweled is to signal that the moment is right for the pleasures of love and in the desire to be beautiful, there is the promise that nothing is more important to the nayika than the loving admiration and attention of her beloved. This is the rite of spring for mankind and nature alike. It is for this moment that she has waited and prepared with longing and anticipation. Yet there is a certain anxiety and apprehension, but in this very state of nervous animation, there is a dedication and a commitment to the celebration of her love. It is clear that the beautiful expressions of Vasanta, and equally the adornment of the nayika, is not mere beautification but it is a rite and a ritual, a promise; for adornment is the bond that ties the beautiful to the beloved, the nayika to the nayaka, the verdant Prakriti to the cosmic Purusha, man to God, asserting that the beautiful and beauty are an integral part not only of romantic love but of the sensually charged mind that luxuriates in Vasanta.     Jayadeva describes Vasanta with these words:

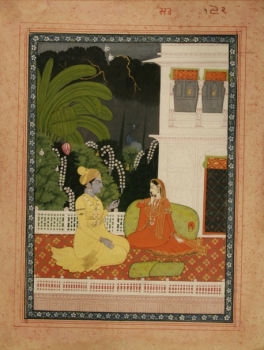

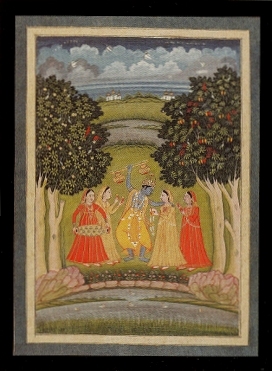

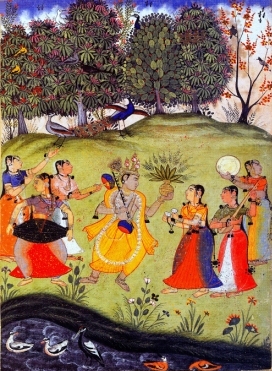

If poets like Kalidasa and Jayadeva capture the essence of Vasanta and the mellifluous love of Krishna in words, it was left to artists of the Pahari kalam to depict Vasanta in paintings. It was in the later 18th century that the fully evolved Guler Kalam was taken to Kangra and there under the patronage of Raja Sansar Chand (1175-1823) that Pahari lyricism found its highest perfection. In the subdued colours and charmed landscape of Kangra paintings, as seen in the Lumbragaon Gita Govinda among others, the tender love of Krishna and Radha is almost palpable and one can hear the sweet whisper of their conversation. The Kangra psyche was conditioned not only by the geography of the environment but also the history of the prevailing times. Kangra was blessed with an idyllic landscape, with blossoming trees and verdant groves, sylvan hills and distant mountains, picturesque meadows, fragrant flowers and chirping birds, flowing brooks and a clear sky that provided a canopy to the enchanted world below. There was here none of the harshness of the Rajasthan deserts or the sweltering summers of Gujarat, the courtly intrigue of Rajasthan courts or the enforced privacy and distance of the Mughal harems. Although there was political intrigue in Kangra, there were no major wars or military strife, the rulers were benevolent and patrons of the arts and leisure and culture flourished both with the raja and the praja. There was a certain joyousness and sensuality in the 18th and 19th century Kangra court as is seen in the accounts of Western travelers like Moorcroft. It is not surprising that the Kangra artist was to incorporate this ethos in their kalam and used it to portray the madhurya of Krishna and especially the heart throbbing romance of Vasanta.. It has been rightly said that Kangra painting is characterised by a lyricism, a patrician elegance tempered by a simplicity and warmth of feeling, a refined earnestness plus a suavity of form. These paintings are kavyamaya, suffused with the lyricism of poetry, layamaya, full of the delicacy and softness of dance and gitamaya, resonant with the sound of music. Emotion is almost palpable, tender feelings of Krishna and the gopis are visible and the music in the air is audible in these beautiful paintings, but only to those who have the sensitivity to go beyond the surface and partake of the nuances and suggestions of Krishna's romantic moments with the gopis. In their time, these paintings must have been celebrated in elite and cultured company, in sophisticated and elegant surroundings, with the accompaniment of song and dance, with flowing madira and smouldering hookahs and not silently watched in the sterile ambience of a museum or in the mute pages of a book.   It has rightly been said that Kangra painting is the superb lyricism and the melody of the sweet love of Krishna made visual. The landscape in the paintings which is inspired by the bucolic and luxuriant Pahari terrain is assimilated to the mood of the personages through a symbolism that is very transparent in its poetic suggestion. While the Kangra kalam exudes a refined sensuousness and lyrical grace, drawing its inspiration not only from its idyllic landscape especially of Vasanta, but equally by the living presence of the Krishna of love in the courts, it is in the depiction of the graceful and elegantly sensuous shringara rasa nayika that it reaches its greatest heights of artistic finesse and mastery. The Modi Bhagavata and the Lambargaon Gita Govinda rank as the highest watermark of the magnificent Kangra kalam. The Kangra nayika of painting not only has an elegant and sensuous charm, a luminous elegance and unsurpassed beauty, but a refined romantic sensibility, whether she was experiencing the pain of pathos of the pleasures of love, and in the genre of romantic figures that Indian artists have produced, she represents the most beautiful and the most exalted. There is in her not only the charm of romantic sensuality but the serenity of a woman in love who is also aware that her sensuality is the doorway to spirituality. Vasantaotsava or the festival of spring was an important festival that was celebrated in ancient India and it venerated Kama. Kama was also called Manmatha or the one who churns the mind. Kama is the god of love, who rides a parrot holding aloft his fish banner, raising his sugar cane bow and drawing his bow string made of bees to shoot flower arrows at unsuspecting maidens. This festival of spring is ancient and finds mention in Sanskrit literature. Harsha's 7th century play Ratnavali opens with a description of Vasantaotsava:

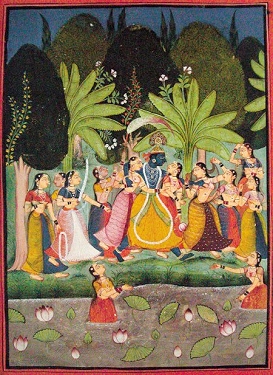

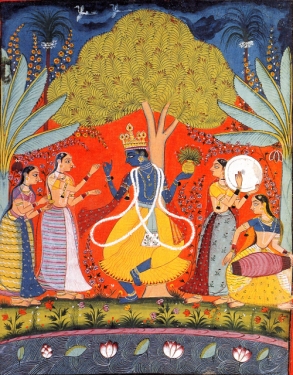

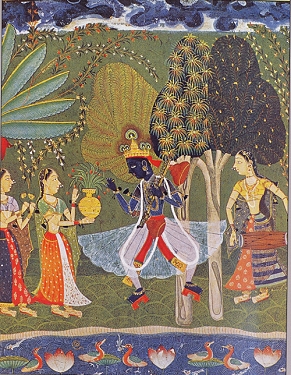

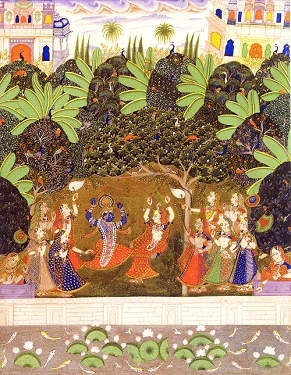

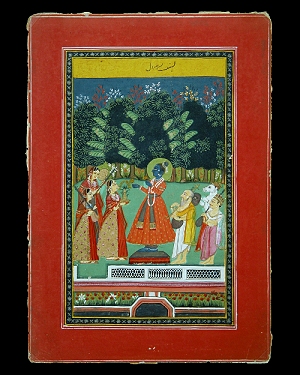

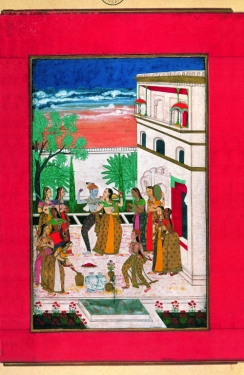

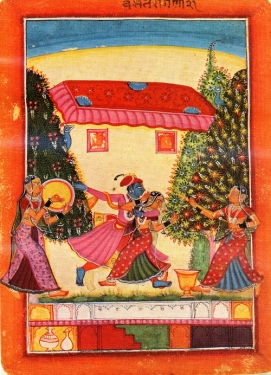

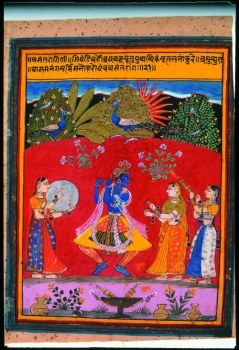

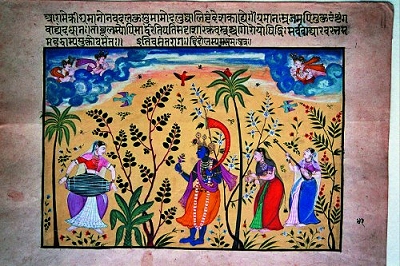

Sagarika, the heroine of Ratnavali, also observes that while the God of Love is worshipped in an iconic form (pratyaksha) in her father's home, he is worshipped in a painted version (chitragato'rchyate) at Kaushambi. It is fair to assume that creating patachitras of Vasantaotsav were prevalent in ancient India. Kalidasa's Malvikagnimitram and Madana's Parijata Manjari are plays that also extol spring festivals and were performed as part of the celebrations of spring.     The evolution of the celebration of the Vasantaotsava has evolved from a festival of Kama in times ancient to that of Krishna, and in this transformation there is an important shift in the way shringara was celebrated and understood. In the past, Vasantaotsava was dedicated to the worship of Kama. At this festival of Kama, young women would wear blossoms of the Ashoka in the ears as this is one of the flowers of Kama's bow. The other four flowers were the mango, the blue lotus, the red lotus and the jasmine. This was one of many rites of spring, celebrating not only the end of winter and a time for growth, but equally a recognition of the importance of human love and nature's fertility in the Indian tradition. It was a time mainly for women to celebrate and express their pent up passion but ancient texts also describe the king participating in the festival, and in the spirit of festivity, at this festival social and caste barriers were dissolved. Coloured powders and liquids, derived from flowers, kumkum, gulal, musk, and sandalwood were sprinkled and sprayed into the air and onto each other as men and women mingled in joyous abandon. The festival had both a romantic and erotic connotation. The drenching of a woman with blood red colours not only sanctified her fertility but equally was an invitation for amorous pleasures. In its ultimate analysis, Vasantaotsava is celebration of kama as desire and also Kama as deity. In the Vishnu Purana, Pradyumana is mentioned as the presiding deity of the Vasantaotsava. However gradually Kama was replaced by Krishna as the main deity of Vasantaotsava and the spring festival was observed as Holi. In replacing Kama with Krishna, the message clearly was that shringara should move away from desire to devotion, from sensual kamana to spiritual bhakti. It is Krishna, who through his amorous involvement with the gopis in Vrindavana reminds us that while shringara activates the atmani vishnum, dormant streams of honey in one's atman, that true realisation or atma darshan can only come when the sensuality of romantic love is transformed into the spirituality of love and when sakar prem is changed to nirakar prem. This is the meaning of Krishna's madhurya and it acquires a very different texture and meaning from kamama and is the essence of the shift in the presiding deity from Kama to Krishna in the celebration of spring. Krishna's association with Vasanta is also celebrated in Ragamala paintings. In these paintings Krishna is shown dancing with the gopis. The iconography of Ragamala paintings varies from one school to another. However, one particular raga that follows a consistently uniform iconography in the various schools of painting is raga Vasanta, which always depicts Krishna as the main protagonist. It invariably shows female attendants accompanying him, playing musical instruments, particularly the tabor, daphli or drum, dhola. Some spray him with water syringes, others dance in joyous abandon. It has been suggested that the iconography of raga Vasanta draws upon the imagery of Vasantaotsova.

The foreground is an unusual pink colour. There are gold pitchers, presumably with coloured water and syringes. Clumps of yellow and white flowers, delicately tinged with red and finely drawn leaves may be seen. The middle ground which occupies half of the canvas is a virulent lacquer red. It depicts three women and a male dancing figure. One woman beats upon the tabor, the other upon the cymbals and the third sprays coloured water from a syringe. The faces of the women are of the Mewari type with large fish-shaped eyes, small eyeballs and heavy jaws. The ghaghra, choli and odhni are variegated and delineated with care. The bonbons edged with pearls are attached to the ends of the bangles, armlets and braids. Ananga or the God of love amidst the females is certainly Krishna. He is easily identified by his crown of peacock feathers or moramukuta, a garland of forest flowers or vaijayantimala, pitambara or the yellow dhoti and, above all the flute that he is playing. Mughal influences may be seen in his attire as also the flora in the foreground and the middle ground. The lilies in the red ground, the finely drawn serrated leaves of the rose in the foreground are similar to those painted on the hashiyas of Mughal miniatures in the period of Jehangir. Such clumps of grass and flowering shrubs which are not indigenous to Mewar are also seen in the landscapes of Kangra paintings. The flora in the background has the flowering Mango, Banana, Champaka and also the flowering Ashoka trees. All these (except the Banana tree) are mentioned specifically in the context of the Madanotsava festival. Peacocks signifying lovers may also be seen. It is unusual that the main ground is a virulent red instead of green which is more evocative of Spring. Scholars have tried to explain this by harking back to the Mewari tradition of using saturated, primary colours, specially red, for dividing the pictorial space into different zones of action. However, this is not the case here as the colour palette of the artist is sophisticated. One notes the delicate shading in the painting of the flowers, diaphanous uttariya, striped pyjamas and the dresses of the women. The reason for the red ground has to be sought elsewhere. Madanotsava was observed at sunset and it is entirely possible that the red palm tree in the shape of the setting sun energises the entire landscape and touches the kalam of the artist who chooses to work with the colour red. The depiction seems to adhere closely to the type of Vasantaotsava chitras that were painted for the worship of Ananga; however in raga Vasanta, Krishna replaces Ananga. It is also possible that the padas or lyrics sung for worship here may have been composed in the Vasanta raga.   Even up to the 20th century, the compositions of Raga Vasanta are deeply connected with the Krishna festival of Holi at Braj and the flowering spring season. The following well known composition evokes the mood of both Holi and Spring:

While conforming to the basic iconography of raga Vasanta, different schools create their unique version of this quintessential raga of Krishna. Each school while adhering to the basic iconography depicts Krishna, dancing and frolicking with the gopis in a luxuriant and verdant environment. Whether in the Kangra paintings of the Gita Govinda or the various Ragamala paintings of ragini Vasanta, the central figure is that of the dancing Krishna. Krishna's movements resonate with that of the leaves and the branches, his rhythms match those of the birds and the blossoms, his gestures of sweet love touches the gopis who tremble with excitement in the celebration of Vasanta. This is Krishna's dance of joyous awakening, and He radiates this to the world around him which becomes alive with the pulsating and trembling excitement of love. This is the essence of Vasanta for Krishna. However, when it comes to the barahmasa songs and their paintings, Vasanta takes on a poignant meaning. Shadrituvarnan or the description of the six seasons, vasanta, grishma, varsha, hemanta, shravan and shisira is an important part of the kavya literature in Sanskrit. However Sanskrit literature did not have barahmasa poetry. It was apabhramsha literature, precursor of Hindi, that developed a rich description of the seasons and tied to romantic love. In this genre, there is chaumasa, poetry which had either four or six seasons or barahmasa which was a description of the seasons of the twelve months. The vernacular and oral barahmasa later becomes an important part of the literary poetic tradition, both secular as well as Hindu, Jain and Sufi religious poetry. While religious barahmasa remains didactic in nature and were used to impart religious instruction, the village chaumasa and barahmasa were romantic and were village women's rain songs, especially in North India from Gujarat to Bengal, where they sang of their isolation from their husbands either in the rainy four months from ashada to ashvin or through the twelve months. These rain songs are based on the sociology of the absent husband, who is away from home either on business or duty, and the wife either longs for his return in the rainy season or urges him not to leave at all. Seasonal poetry of this genre also was a feature of folk theatre. There was some variation not only in the number of seasons but in their chronology as well, and one of the poetic conventions was that while Sanskrit shadritu poetry described the erotic joys of the lover and the beloved when they are together, the chaumasa and barahmasa dealt with the premika's longing and fear of separation from her beloved.  Keshavdas in his barahmasa converts the lunar calendar into romantic poetry that vividly celebrates the months as it evokes the pain of the nayika of the impending separation from her beloved. Starting with the month of chaitra, he portrays the heroine urging her beloved not to leave her in that month as every month has something special which would make separation painful and unbearable and as the poet goes through the twelve months, the heart throb of the nayika pulsates with the sap and songs of the world around her. This is how Keshavdas describes the two months of Vasanta.

Harsha V Dehejia has a double doctorate, one in medicine and the other in Ancient Indian Culture, both from Mumbai University. He is a practicing Physician and an Adjunct Professor of the Division of Religion in the College of Humanities at Carleton University in Ottawa, ON., Canada. His special interest is in Indian Aesthetics. He has 12 books to his credit. He writes mostly on Krishna. |