|

|

|

|

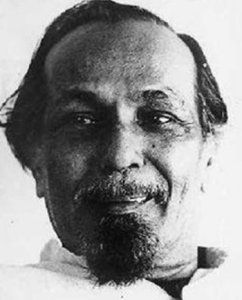

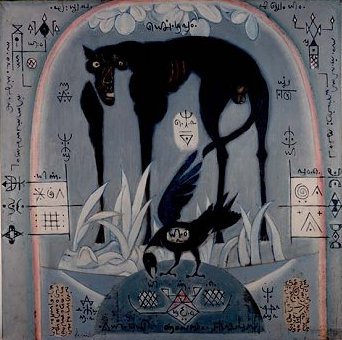

KCS Paniker: His art and his times - Padma Jayaraj, Thrissur e-mail: padmajayaraj@gmail.com September 22, 2010  Kerala Lalitkala Academy, recently celebrated the birth anniversary of KCS Paniker, a doyen among South Indian painters. The seminar evaluated Paniker from the perspective of his times. Those who spoke were reputed art historians, academicians, and critics. Interventions from a discerning audience made the day intellectually alive. KCS, no doubt, stands tall in the world of South Indian art and painting after Ravi Varma. Both of them hailed from Kerala, went out to create an art world with a pan-Indian stamp, made history, and left a legacy. But instead of glorifying an iconic figure, with an irreverence that characterizes the Malayali spirit, the discussions deconstructed Paniker. Sadanand Menon, Sivaji Panikker, and Ashrafi S Bhagat were some of the speakers. They dwelt on three aspects: KCS, the artist, the 'Madras Art Movement' he started, the Cholamandal Artists' Village he founded, and his legacy. KCS: The Painter Kovalezhi Cheerampathoor Sankaran Paniker (May 31, 1911- January 15, 1977) carried the imprints of the water-logged landscape of Kerala, its life, arts, and philosophy when he moved out in early childhood. His career as a painter moved through three distinct periods. His early paintings, in water colors, depicted the wonders of rural Kerala. In the second phase, the rustic people with a distinctive Dravidian stamp marked his humanscape. The final segment had a visual language culled from symbols and motifs from Kerala's arts and metaphysics. Paniker was a child prodigy who began painting at eleven. His early paintings in water colors are luminous: the sun-dappled coconut and areca nut farms, green swaying fields, sunlight and shadows creating patterns where humans form a part. Rivers, ponds, sandy plains, and village scenes bathed in colors of dusk, are visual treats. Living in the arid land of Tamilnadu, the artist nostalgically captured the pristine beauty of Kerala's scenery, the lost horizon of his childhood. They are realistic representations with personalized brush strokes that carried features of the 'abstract.' Romantic and decorative, these pictures filled the forties.   When he started his humanscapes, it was the rural folk that filled his canvas. His preoccupations with the Ajanta narratives started in early fifties and led him to the sculptures of the Chola period. By mid fifties, Paniker had gone through the whole gamut of his experimentation with human forms. Like Kerala's murals, the background depicted its crowd. The boatmen, the Muslim fishermen, the fruit seller, crowded market, pregnant women and other paintings recorded the rhythms of a rural ethos. 'The Farmer of Malabar' communicates at the level of theme, form, and aesthetic enjoyment. The picture is the portrayal of a way of life in the history of humanity. A nostalgic visual memory determined the dynamics of many of his paintings. In the Peace-Makers series, the people are reminiscent of figures both real and stylized, in art forms. Indigenous in tone and tenor, simple images with pronounced linearity illumine his canvases. The visual language of KCS recorded the story of a locale, romantic, even Utopian, but rooted in rusticity, human to the core. And his 'Garden series', 'Mother and child' were experimental. He dabbled with expressionism. Meanwhile, his lines gained power with a luminous sense of color. The third stage was a move from the regional to the national, thematically; from impressionistic to post-impressionistic, stylistically. Gandhiji, the Buddha and Christ reveal his secular attitude. The influence of Ajanta is palpable in his works of this period. The stylized imagery in paintings like 'Mother and Child' takes us to Kerala's performing art forms. His grammar was in the making. Soon "words and symbols" series opened a new vista: "...an intriguing carpet of color fields and calligraphic texture, with a distant visual reference to our old manuscript rolls", to quote KG Subramanian. In the seventies, his works like 'Crowd' became animated in bright reds, greens, yellows and orange, the river of life carrying 'Dog', birds, animals, and fish full of echoes of cubism with a south Indian distinctiveness. This visual language was Paniker's defiance to counter alien influences from the West. He used metaphysical abstractions more for visual effects, for mystical conclusions than for any specific messages. From another perspective, 'Words and Symbols' is part of an undercurrent that started from Mohanje-daro. The images, coloring, and style show the influence of the occult and the Tantric of the ritual arts of Kerala. In the words of Paniker himself, "They hark back to the weird, but spiritually uplifting figurative exaggerations of ancient Indian painting and sculpture." 'Words and Symbols' stand as an abstraction of the cultural slice of his milieu. KCS carved a niche for himself as one of the most important painters who evolved a radical pictorial language in 20th century Indian painting. His contributions Paniker studied art in Madras among a group of pan-Indian friends under Roy Choudhari. As the Administrative Head of the Madras School of Arts and Crafts, KCS Paniker gave an impetus to art as a movement. An anti-intellectual atmosphere prevailed there as he worked with dedicated students. He gave attention to each individual artist, gave freedom and the ambience needed for an artist to grow and flourish. Groups of students used to go out to bring in traditional patterns from the world of craft. This practice inculcated a strong sense of line, form, and rusticity. This created a template of designs which formed the basics of the 'Madras school.' Historically, in India the artists came from the community of artisans, and craftsmen, and left their contribution to posterity without marking their names. Art endured when generations of artists were lost in the mists of time.   But Paniker, with a modern outlook, brought visibility to Madras artists by conducting periodic exhibitions in Mumbai and Delhi. His period witnessed the dynamics of the regional manifestation of modernism in art in relation to a unique search for 'Indian-ness' under the leadership of KCS. KCS encountered western influences during his visit to Europe and England. The face to face with other realities pushed him to take a stance. As an artist, he battled against Western influences, unleashing a storehouse of deathless energy from the confines of myth and 'nativism.' Inspired by Jamini Roy, Paniker found his roots in his regional confines. His art brought a reinvention of the regional at a time when regionalism was resisted politically. A pioneering voice, he gave a modern interpretation to tradition. Many absorbed his idea of the 'indigenous' as a kind of native identity in terms of myths, lines, motifs, folk rhythms etc. And Paniker worked for a school that searched for an identity rooted in home-grown art and craft. Orientalism formed the soul and spirit of his third phase, with 'Words and Symbols' series.  KCS played a key role in bringing the South Indian artists out of the crisis of self confidence. Paniker launched the artist in national forums, gave him dignity, pride, and freedom. A painter himself, Paniker gave a lifeline to contemporary Indian art in Cholamandal. Many painters and sculptors lived, worked and established themselves along with its founder. Their accomplishments made Cholamandal a success and created a legacy for KCS. The self-conscious picture plane that Paniker created remains another aspect of inheritance. A group of urban artists hit upon the use of tantric signs replete in India. In the Fine Arts College, these signs closed in as a restrictive language, taking a conservative stance. Paniker himself warned against the neo tantric that he initiated. But the Madras School produced internal 'orientalism' as a position of power, which can be considered a retrogressive today. Paniker rejected the patronage of Ford Foundation while at the helm of his institution. In later life, he rejected the 'Padma Shri', a coveted honor from the Indian government. Truly, he was an artist who stood for freedom, practicing art for art's sake. And, he remained a humanist, eclectic, wild, and unconventional. Padma Jayaraj is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to www.narthaki.com |