|   |

|   |

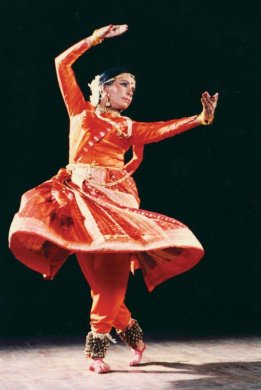

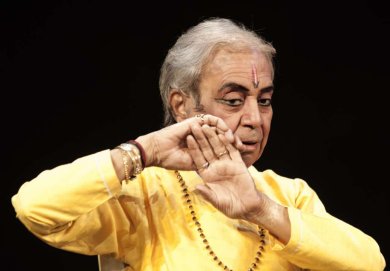

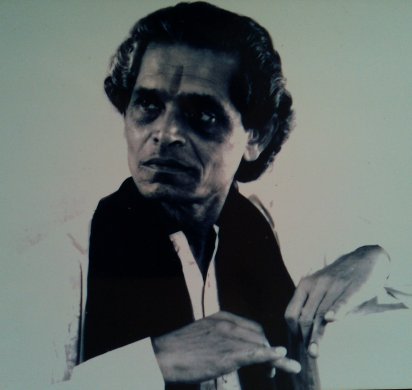

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Back to the roots in Nupur Zankar’s marathon Sanskriti Mahotsav on Kathak Gharanas Photos courtesy: Nupur Zankar May 28, 2021 Watching the nine day virtual Sanskriti Mahotsav curated by Shila Mehta for her organisation Nupur Zankar on Kathak Gharanas, could well have made many wonder ‘why again get stuck in the gharana zone, instead of moving ahead to something of relevance today?’ But dedicated to Birju Maharaj, the reigning czar of Kathak, and his shishya the Late Guru Pandit Vijay Shankar (who the Maharaj affectionately called his Gopi) and to the recently departed scholar/critic Sunil Kothari, this entire enterprise, as explained by the curator, was to make use of this period stripped of the performance fever, to go back, ponder and have a quiet relook at one’s roots, for as Shila very pertinently remarked, “Deeper the roots, taller the shoots.” Tradition survives by accommodating the present and hence while accepting the constancy of change, the need to reassure oneself of being deeply rooted. In what was a painstakingly ambitious enterprise involving gurus of all gharanas, performers pertaining to three generations, providing space for what went as interactions, the flawless organisational finesse had to be lauded. Neatly put together, this set of video material would make an excellent Kathak information tool for the dancer seeking answers to several queries in the mind. The painstaking manner in which the genealogy tree tracing the lineage of each gharana has been tabled makes for good historical reference. The best part of the entire effort was its non-judgemental approach, allowing performances to speak for themselves. And very thoughtful indeed was making the entire effort in support of spreading awareness about Autism. This kind of caring gesture is most needed to negate opinions often expressed about India’s traditional dance forms living in a world of their own, cut off from society and its everyday problems. The short introduction on Autism control by Dorothea Reyman as a curtain raiser for the Sanskriti Mahotsav, makes a strong case for people to understand and realise that Autism is a more frequent occurrence in society than one realises, manifesting itself in different forms – and to be informed, is the starting point of providing support to those who are in need of it. And what a surprise it was to listen to Sandhya Raman who has helped design many a costume for dancers of the Mahotsava about her working with young people with Autism – to discover to her delight how highly their aesthetic feel for colour helped her costume choices. The thoughts of a dancer on various aspects expressed by Shila Mehta at the start of each day of the Mahotsava, coming from deep introspection, apart from being expressed in impeccable language in the shortest possible time, touched on issues of endemic relevance in the art field that every dancer needs to ponder on. Not spoken from a pedestal of arrogant authority but from a consciousness of ‘vulnerability’ as the speaker herself admitted, each of these points needs to be reflected on. Gharanas in Kathak have been often caught in a confrontationist attitude against one another- and it was good to hear Shila speak of the gharanas more as different flavours of a dance form – giving it variety like flowers of a garden in varied colours. What she says about the guru/shishya for me was significant, of the relationship working through chemistry between the teacher and the student (which in answer to a question during the interaction session, Maharaji confirmed, comes from a long guru/shishya association). The guru empowers the student, bestowing on him knowhow – giving him the tools of the discipline, showing him the road - on which the further journey has to be taken by the shishya. Given the form, it is left to the student to work to attain that state of formlessness. The shishya sans an ego (like the empty vessel which can be filled) is the one who ultimately derives the most out of the guru. Both in the giving and in the receiving, the attitude of both guru and shishya is what determines the extent of success in this relationship.  Shila Mehta  Durga Arya Going through the programme videos, reflecting on that ineradicable something defining a gharana, which from a guru is passed on to the student, and which, no matter what the circumstances, remains an internalised, undiminished part of the dancer, I found it in the dance of Durga Arya, a brilliant shishya of Pandit Birju Maharaj (also trained under Reba Vidyarthi and Munna Shukla), living for the last several years in Germany where she is teaching Kathak. Her projection of taal Dhamaar, or even a posture in Thaat, or abhinaya based on a Bindadin composition choreographed by Birju Maharaj, “Awat Shyam lachak chale, mukut dhare” in raag Desh, was so much what I had seen her do in the Kathak Kendra as a student decades ago, and with the same intensity, that for me time stood still – and it set one thinking about that alchemy , which even with so many years away from the soil nurturing the art form, had remained intact without getting nullified. Ultimately the artist’s journey is one without any certitudes working diligently towards what every great artist manages to attain in a lifetime – transcending moments, touching a state where all identities dissolve. These are the moments when an art practitioner becomes a true artist - and such moments are rare. Just perfection of technique in a person does not make him a true artist. Great artists are venerated for attaining that blissful state-of-being, which envelops the audience too wherein for moments, the persona of the artist and individual identities have ceased to exist.  Maya Sapera  Chitresh Das institute As a case in point, while referring to the individual contributions of the Lucknow gharana gurus, Ishwari Prasad was merited (by Shila Mehta) as having contributed the Ganesh Paran. If so, strangely today, it is the Jaipur gharana dancers who present Ganesh Paran and never have I witnessed one from the Lucknow gharana present this. When questioned on this point, this critic could not fully comprehend Saswati Sen’s answer which mentioned something ‘about strong Kali Paran’, and how this related to the question asked was not clear. It is true that gharanas in constant flux cannot be thought of in frozen terms, even given the clarity of compositions in Kathak attributed to specific sources. Today, amidst large Indian diasporas in different countries running schools of Kathak abroad, the art form, while retaining the broad contours, could well acquire new characteristics.A special Kathak day in the United States calendar of art events, quite unthinkable a few decades ago, is without doubt, a feather in the cap of late Guru Chitresh Das to whose credit goes this achievement. And yet the Kathak he taught in his school was for many Kathak diehards, sans any gharana vintage. Having witnessed, during the Guru’s lifetime, his excellently trained students in the feat of singing the lehra (musical refrain), reciting the parhant (recitation of rhythmic syllables) while simultaneously performing the nritta add-forms, I have to admit that this critic, in forty years , has not witnessed anything similar in any other student of any Kathak gharana. Today, the same Chitresh Das Institute performing an uncomplicated Mughal court dance or Agni, with music provided by none other than Alam Khan, son of late Ali Akbar Khan and Isani Basak’s tarana set to raga Jogkauns, while well rehearsed, in the absence of the guru, does not reflect the old fire. Individual gurus, in any dance form for that matter, after having had their training in a gharana, have used their own creativity to create over a period of time, dance which does not pertain to any specific school. “It is dance that matters and few are concerned about which strain of the form it belongs to”, as mentioned, emphatically by a senior most dancer/teacher cannot be denied – except that the theme of this Mahotsav was the gharana. And this wisdom apart, gharanas while understandably possessive about one’s identity, do get into antagonistic postures. In the Benares gharana projection, one found Sunayana Hazarilal’s description of the Benares Janakiprasad gharana very succinct, without the dancer going into any needless hagiography about her guru, who she described ‘as a direct descendent of one who served the court’. Tracing its descent from Sanwaldas of the Kshatriya clan of Chauhans from Bikaner State (and these families used to speak in the Rajasthani language), Janakiprasad later permanently settled down in Benares. Being a Sanskrit scholar, Janakiprasad and Hazarilal added a vocabulary of Natwari symbols aurally pertaining to sounds created by the footwork on the ground – outside the scope of the tabla and Pakhawaj bols. (The parhant apart, it was the musicality of the tabla accompaniment during Sunayana’s demonstration, which struck me particularly). She explained how her guru/husband stressed angikabhinaya and maintaining beauty of prescribed body line, even while coping with speed of footwork or emotions. The khandita portrayal in “Na manoongi na manoongi” and the pithy but strong Kali Paran she demonstrated stood out.  Sunayana Hazarilal  Vishal Krishna Vishal Krishna’s performance on the other hand, with a combination ofvigour, grace and acrobatic chakkars also came under Benares gharana. A descendent of the mercurial Sitara Devi (whose father Sukhdev Maharaj, while asserting his Benares gharana descent, had no hesitation in sending his children Sitara, Alaknanda and Tara to learn under Achhan Maharaj and Lucknow gharana gurus), Vishal’s stylistic characteristics on the other hand are a copy of his uncle Gopi Krishna’s way of performing. Given a mixed bag of this nature, we can see how many manifestations the same gharana can spout. And to define a school of dance within boundaries is problematical. As Sunayana Hazarilal pointed out, many gurus from the gharana like Ashiqelal during the riots in 1946-47, settled down in Pakistan - which further explains gharanas operating amidst migrating populations. Dancers often train under gurus from more than one form – like Manjushri Chatterjee who studied under both Shambhu Maharaj and Jaipur gharana stalwart Guru Sunderprasad.  Saswati Sen  Birju Maharaj Saswati Sen, as the premier shishya of Pt Birju Maharaj, touched on the main features of Kathak as visualised by her guru and how he had revealed to her the lyricism inherent in the pure rhythmic syllables. Maharaji himself referred to the beauty of the anga his father and the gharana constantly worked on – the angled and profiled stances, the way the body was held - with the sole idea of adding to the aesthetics of the dance. While Shambhu Maharaj, Guruji’s uncle, excelled in abhinaya with myriad interpretations of each word and line of the poetry and lyric, the third in this triangle of gurus had Lachhu Maharaj with his own genius – which looked at hidden abhinaya moods within nritta compositions. In the snippets of dance films of innumerable creations of Birju Maharaj, one even sees Saswati performing to an ashtapadi, with a screened snippet of her own choreography from her Romeo and Juliet dance drama – presumably illustrating how the form with its alphabet, can extend to choreographing compositions outside the traditional repertoire. Jaipur gharana’s Rajendra Gangani, as a direct descendent of the gharana specialist Kundanlal Gangani, while presenting his well trained students Dhirendra Tiwari and Diksha Tripathi, did not dwell on typical characteristics found in the dance based on his father Kundanlal Gangani’s approach to Kathak.  Dhirendra Tiwari  Prerana Shrimali However, the guru’s other senior shishya Prerana Shrimali, on the other hand, referring to the nritta stress in Kathak (with particular emphasis on the Jaipur gharana) dilated on the ‘absolute abstraction’ within which spaces to express abhinaya also could be found. So central was this to the style that even the musical refrain of the nagma or refrain was superfluous – for the Kathak dancer ‘performed a taal’, and not ‘to a taal’, which explains how the arithmetic of rhythmic syllables finds lyricism with a taal blossoming out like a flower, creating its own magic. If other dances speak of trying to attain formlessness through form, in the Jaipur Kathak one looks for forms within the formless. In illustration of what she said,followed the precision and lyrical quality of the nritta, with a brief abhinaya glimpse through a Raas Pada expressing adbhuta or wonder of Krishna with the gopis based on the poetry of one of the famous Ashtachhap poets, “Aise khili hai alaukik chandani nagarta ko vichaar” and that very poetic “Niratat Gopal sanga gop kunvari ati sudhang…” What one notices in Prerana Shrimali’s dance with kavits knit into the choreography without obstructing the flow, is a smooth enmeshing of rhythm and interpretative dance, where one does not consciously feel the one stopping and the other beginning. Her student Aarti Shrivastava performed a tight 17 matra nritta followed by the mimetic composition based on Raas “rain samay ras kelikiyo.” From Nrityadhaam Pune, Prerana Deshpande, trained under late Rohini Bhate, in her ‘ekal’ nritya, competently brought out that quality of precision and subdued abhinaya - features of her guru’s style.  Prerana Deshpande  Guru Ram Lal Bareth  Suchitra Harmalkar  Alpana Vajpeyi The less prolific Raigarh gharana had the right knowhow provided in the introductory talk by Guru Ram Lal Bareth himself. Suchitra Harmalkar’s performance was particularly impressive. Alpana Vajpeyi is perhaps the best known among Raigharh gharana dancers. This gharana (the brainchild of a brilliantly gifted ruler like Raja Chakradhar Singh, bestowed with phenomenal artistic sensitivity in music/rhythm and dance, also inspired by constantly being treated to Kathak dancers of every denomination, invited to perform in the court), is the only one with its entire theory and compositions preserved in the composite voluminous treatises penned by Raja Chakradhar Singh, carefully preserved in the State as precious legacy. With the royal line disappearing, the gurus without patronage languished in isolated villages till brought back into reckoning – with Gurus Kalyan Mahant, Kartik Ram and Ram Lal Bareth established at the State run Chakradhar Singh Nritya Kendra at Raigarh. But this gharana not being prolifically presented in the rest of the country, has not shown changes. Along with its main format of compositions created by the ruler, plus characteristics it shares with other gharanas, this school has its own flavour. One would have loved to hear Chetna Jyotishi Beohar, a fine scholar of Kathak who has done a lot of work on the Raigharh gharana in particular, to share some of her thoughts. As one who has headed the Kairagarh University of Madhya Pradesh, she has had the maximum opportunities for delving into the original treatises of Raja Chakradhar Singh, the founder of the gharana. Surprisingly, she only chose to present an abhinaya item without saying anything about the gharana. Cited as the forerunner of Kathak and the gharanas, even the ancient Kathakar’s tradition wherein dance featured along with a total theatre form, while narrating episodes from the temple tradition, was not left out of the reckoning. Shila herself presented Amba/Shikhandi from the Mahabharata, of Amba taking her revenge on Bhisma, who with his brahmachari vow, had refused to marry her in her/his previous birth as Amba. For this critic, the surprising moment of the entire event came from a passing comment by Saswati Sen about an ancient undeciphered manuscript in Prakrit, written by Birju Maharaj’s ancestors, which is in Maharaji’s possession! If this indeed be so, one would earnestly plead that an unfailing attempt be made to find a Sanskritologist and specialist (there are many who have worked on Prakrit compositions) to decipher this manuscript. It could yield invaluable information, bridging several years of gap in Kathak dance history! Nupur Zankar has, with aplomb, carried off a Herculean task with finesse!  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |