|   |

|   |

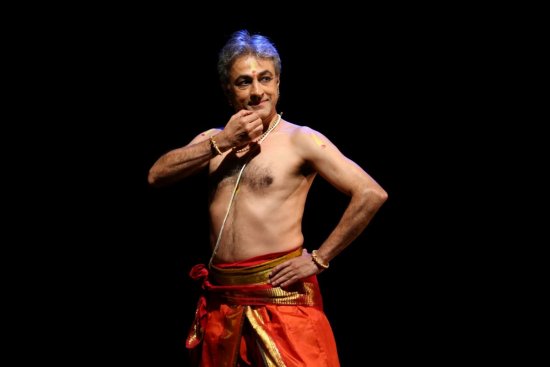

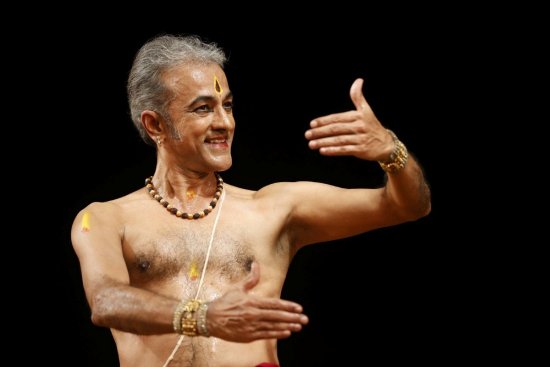

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Exhilarating performances by Sutra, G Narendra and Anandita NarayananNovember 11, 2025 POOLED SUTRA / TRIDHARA RESOURCES REVIVE VIBES OF GANJAM'S TRADITIONAL RADHE RADHE Photos: Kkrishnan Chakraborty Art collaborations between countries, aside from enabling a pooling of artistic resources, can ensure an enjoyable and non-abrasive means of fusing people-to-people relationships. So it has been between Malaysia and India with the Sutra / Tridhara agreements over the years, wherein, the historical research and knowhow provided on Odisha's rich performing art legacies by one group head, have helped translate into showcasing performances, underlined by the refined artistic sensibilities of the other - thus benefiting both inheritors and propagators of an artistic tradition. Collaborators above all, need a generous sponsor for agreements to fructify and aside from the Malaysian authorities of Arts Against Aids and Sai Ananda Foundation Malaysia, one cannot but have admiration for bodies in India, like Kala Kalp Sanskrutik Sansthan led by Dr. Atasi Misra, whose generous invitation to host the Sutra / Tridhara collaboration, at Delhi with a show of Radha Radhe at the Kamani, has enabled the latest Delhi visit for the Sutra troupe. Malaysia's Sutra Dance Theatre under its director Datuk Ramli Ibrahim, who, after years of experience as a western Ballet dancer, took to Odissi in a big way, training under late Guru Debaprasad Das, has found in Guru Gajendra Panda, heading Tridhara in Bhubaneswar, a 'guru bhai', who is a reservoir of historical information and data on artistic traditions of Ganjam, Gajendra's home district. For twenty long years, till Guru Debaprasad's untimely death in 1986, Gajendra Panda was groomed under the Guru, whose profound belief in the heart of a tradition lying in its folk beginnings in rural areas, was based on the conviction of the hidden continuum of the folk and the tribal, within the stylized classical matrix. Ramli's special interest in this part of South Odisha has its seeds in his close friendship with late Dinanath Padhi (also very close to Gajendra), who hailed from Ganjam. One of Odisha's finest painters who was also an art historian, poet and novelist, who collaborated with Eberhard Fischer on several of Odisha's art-ethnological projects, Dinanath nursed a grievance that during the refashioning of Odissi, spurred by the Jayantika meetings, the over- emphasis on the Puri and Jagannath legacy, fanned by various political considerations, cut out South Odisha's traditional art thread from Ganjam completely comprising rich folk dance and theatre traditions of Ram Leela, Bharat Leela, Krishna Leela, Prahlad Natak, Rama Natak etc. It was under his mentorship that Sutra's group offer of Ganjam, a path breaking work, was propelled, and evidently Dinanath had urged during his lifetime that as part of the tribal/folk continuum of the Leela traditions, the essential spirit of the rich tradition of Radha Prem Leela with its credentials of music, and theatre be looked into, for being brought onto the international stage of present day Odissi, as a very significant part of Odisha's Kalinga tapestry - showing also how the Desi and the Margi are not totally inseparable strands ,as one would believe.  Radha and Krishna After combined visits to the Ganjam village of Putabagada to watch the folk theatre of Radha Prem Leela celebrating the Divine spring time, love play of Radha and Krishna built round the Manobhanjana episode from the Rasa chapter, which held them enthralled with the lasya filled dance and the extremely emotive singing in the typical traditional style, the desire to incorporate its essential vibes to showcase in the present Odissi Margi system, climaxed into in a year-long preparation, involving stalwarts of various fields who worked with Gajendra Panda. Fortunately for the producers, the most characteristic feature of Ganjam's Prem Leela which is its music, set to typical south Odisha ragas with its slow spun singing style (not easy to adapt for movement strung to present day Odissi), had already been worked on to an extent, years earlier by Dr. Santanu Kumar Rath of AIR, for projecting the music of Radhe Radhe in an hour's programme on AIR - and his willingness not only to provide a copy of the recording, but to engage in discussions with Gajendra Panda and music experts helped. Involved in the music composing and rendition for the Odissi Radhe Radhe were Guru Dr. Gopal Chandra Panda with his deep research into the Odishi music tradition, along with his singer /daughter Sangita Panda, while Satchidananda Das, the rhythm and mardal expert, looked after the nritta part and Dr. Santanu Kumar Rath composed the libretto. Not the least of the experts was artist Bibhu Patnaik, whose delightful Patachitra drawings as backdrops, inspired by drawings from palm leaf manuscripts, provided a special dimension of aesthetic authenticity to the production. The earthy flavour, above all, came from the vocabulary of traditional rhythmic syllables (bols) of Prem Lila, which was retained, while set in the present Odissi matrix, closer to the Margi tradition. Gajendra Panda himself is known for his flair in composing Sabda Swara Pata compositions, combining the verbal and the mnemonic, as in Kathak Kavits - a feature of Guru Debaprasad's style. The challenge was in invoking the vibes and artistic flavour of a pristine performance tradition, in a present Margi format from Mangalacharan to Sthai, followed by Pallavi and Abhinaya in the present concert fashion.  Radha and Krishna The storyline of Radhe Radhe is uncomplicated. With Radha and Krishna attracted to each other, Radhe waiting for Krishna in the forests of Brindavan for the promised tryst, is anguished by the non-arrival of Krishna - who on his way to meet Radha, is waylaid by another nayika Chandravali. When Krishna finally makes an appearance, he is taunted by Radha, who, in anger and anguish, points out the signs of betrayal all over his person. Crestfallen and repentant, Krishna tries to win back Radha in various ways. Finally relenting, Radha yields and the couple is lost in sweet surrender. Propelled by divine music, Sutra's group presentation, was a feather in how co-artistic direction and dance composition between Gajendra Panda and Ramli Ibrahim had worked. The group discipline in the Sutra dancers was delightful. Ramli must have toiled very hard to achieve such group harmony - because Sutra's recent crop of dancers no longer comprises artistes from the old team - all excellently finished performers, who, for years, served and functioned like a well-oiled machinery. The only known faces one now recognizes are of the now more mature, vivacious lead dancer Geethika Sree and Tan Mei Mei.  A dejected Radha and guilty Krishna In the opening Sri Radha Dhyana Sloka, set to ragas Punnaga Baradi and Khambabati, Radha deified as the feminine principle and Krishna as the masculine principle are invoked, symbolizing the eternal principle of spiritual longing. Sthai, which is predominantly nritta, its vocabulary inspired by folk movements, set to ragas Panchama Baradi and Vajrakanti, has a unique treatment, wherein through the patterns of rhythmic syllables, twin moods of sringar are introduced - one of joyous expectation represented by Chandravali as the vasakasajja preparing herself to meet Krishna, contrasted by the image of Radha as khandita, waiting in vain for the errant Krishna. Odiya Abhinaya constitutes the next item performed to Krishna Chandra Deba Narayana Gajapati' s composition "Adha Adhara Samudhara" in raga Abiri set to Ektali, with a brief reference to Krishna's mischief on the one hand and to his feat of holding aloft Mount Govardhana, thus protecting and shielding the citizens of Vajra from a calamitous end through floods. The composition also evokes Krishna in his manifestation as the worshipped one and beloved of Radha and as the Raas dancer who satisfies all the Gopis. The Pallavi in Kiravani based on Lakshmi Kant Palit's musical score, again based on rhythmic syllables, was cleverly choreographed to suggest fleeting moments evoking sringar, the movements based on Ganjam's folk traditions.  Kiravani Pallavi Geethika, in both movement grace and expressional finesse makes an excellent Radha, the grace and sculpted motionlessness of frozen one-legged stances, with torso in an opposite, graceful abhaya bend a delight to behold. Tan Mei Mei makes a convincing Chandravali and all the male dancers (none of them from the old group) Harenthiran, Jagyandatta Pradhan, Ashikar Raj, Vanizha the Birdseller, Rajavel as Bhagavathar, also move well with unerring sense of stage spacing. The Bhagavathar Rani was Prithyalasmi. The delightful Patachitra paintings at the back, on which appeared the briefest of one-liner explanations for each stage in the development of the story - cut out needlessly long winding introductions, enabling the story to move at a fast clip. But the organizer's longish intermission before the last scene, interfered with the mood buildup, in a needless stopgap event with VIPs on the stage, replete with garlanding formalities - all of which should have been before the start of the show. Thanks to Gajendra Panda's efforts, barring a passing musical phrase, when Sangita's vocal cords seem to have played false, the music and accompaniments stole the thunder. Costumes were aesthetic and for this critic, the event was a wonderful example of an artistic loka dharmi / natyadharmi blend. Apart from sponsoring the show, Dr. Atasi Misra's Kala Kalp Sanskrutik Sansthan gave a start to the evening with her students presenting, after an instrumental music invocation playing "Ahe Nilo Sahilo," a brief Ganapati dance homage to "Vighna Vinayaka Siddhipate," wherein the danced episode showed how Ganesha acquired his elephant head and his various other accoutrements. Next followed Atasi Misra herself presenting abhinaya visualized by her Guru Debaprasad - "Mohane Deli Chahibo." She had also participated in visits to the village to watch the Leela episodes, and hence her interest in Radhe Radhe. DAZZLING VIRTUOSITY OF G. NARENDRA'S BHARATANATYAM Photos: Ramanathan Iyer But for the two-day festival at the Triveni auditorium, Delhi, curated and executed by Dr.Sahana Selvaganesh, a Bharatanatyam student of Roja Kannan, under the aegis of an NGO Nirvikalpa started by her and her friends, the Delhi audience would not have had the chance of being treated to a performance by the very senior, established, Kalakshetra trained Bharatanatyam dancer G. Narendra. Before discussing his performance, one needs to express words of appreciation for young Selvaganesh's initiative in holding such an event, which apart from performances by a blend comprising many young dancers, with some senior artistes too, included discussions - with lively exchanges among the dance coterie - a feature totally lacking in our performance calendar. One received very enthusiastic comments about the early morning panel discussion featuring Geeta Chandran, Gauri Diwakar and Priya Venkataraman, moderated by Dr.Sahana Selvaganesh and Revathy Anantakrishnan, followed by short performances - which unfortunately for persons like this writer living outside of Delhi, became difficult to attend during the morning hours. More such discussions are the need of the hour. The first evening began with a short projection of Mohiniattam by students of Jayaprabha Menon, whose training was under K. Saraswati, Bharati Shivaji, with later influences under Kavalam Narayana Panickar. Starting with a Kavalam Narayana Panicker composition on Ganesha "Paripahi ganadipa basura moorte" in Saveri, the well trained dancers went on to a composition in Suratti, composed by Kavalam Padmanabhan (a non dancer who through compositions made a great contribution in defining the regional specifics Mohiniattam should be built on) highlighting the chuzhippu, andolika, atibhanga and body technique of Mohiniattam, and concluded with an ode to Bhumi Devi Bhuvendanam, a composition of Kavi Vallathol, in Arabhi ragam, where a Bhoomi Suktam pays homage to Mother Earth. The recorded musical support comprised Kottakkal Jayant with Satish Poduval's vaitari.  G Narendra Now in his sixtieth year, and slated to receive the Nritya Choodamani award, exceptionally gifted artiste G. Narendra has unfortunately not received his due from the art sponsoring government bodies - and with performance opportunities too being far and few between, for Delhi audiences to get a chance of seeing him in action would have been well-nigh impossible, but for Nirvikalpa. It was a modest gathering at the Triveni, treated to a performance of exceptional virtuosity, with the dancer interpreting a Varnam in Tamil, "Pavanam tanda bhuvana Mudhaley" on Hanuman, composed by Professor G.Raghuraman, the Tamil scholar, and set to music in ragam Reetigowla by Kalakshetra's acclaimed vocalist Hariprasad. The dance interpretation was by Narendra himself. While the Hanuman epic is popular, this son of Kesari, the monkey God, is also known as Vayu Putra (son of Vayu), Vayu believed to have blessed him with wind speed by carrying Shiva's spiritual energy to mother Anjana, a celestial nymph, before Hanuman was born. The Varnam's sahitya references comprised known episodes of Hanuman, as a youngster, trying to grab the Sun God, being finally blessed by him with special powers, powers which helped Hanuman destroy Lanka. Rama's supremacy owed a great deal to Hanuman's never ending loyalty and help and Rama is ever beholden to this monkey God, for his feats - in speeding through the air, carrying the uprooted Drona Mountain, on slopes of which grew the rare herb Sanjeevani, needed as a last resort to save the life of battle felled Lakshmana, and for successfully discovering abducted Sita's whereabouts in Lanka, ending her long agony in incarceration, by handing over the Chudamani with the news that Rama would soon arrive to free her. Narendra's passionately involved recital inspired, and was in turn fired by the supporting accompanists, with the Kalakshetra colleague of Narendra, Mahalakshmi conducting with her spirited nattuvangam. K. Venkateswaran's soulful vocal support keeping up with the dancer's moods dictated by manodharma, mridangam mastery by M.V. Chandershekar, with G. Raghavendra Prasad's tuneful violin, comprised the team. The audience watched in awe the linear exactitude of Narendra's dance profile - astonishing in one of his age! Taking off from the center of a well pronounced araimandi stance, not even in youngsters does one see the hand stretched backwards with the head turning fully following the hands in a taut straight line from the shoulder. As for the interpretative part, Narendra was always known for his excellent abhinaya. The twinkle footed jatis provided the right punctuation between sahitya lines.  G Narendra Without taking away from the stamina, zest and brilliance of a non-stop performance spread over an hour and a quarter, and the fact of Narendra's fully succeeding in creating in the rapt audience the complete suspension of disbelief with the antics of Hanuman, I wish to raise a question which nagged me. And that is about how much of lokadharmi is permissible in Margam Bharatanatyam. I remember, years ago, feeling somewhat uneasy while watching Padma Subrahmanyam in a recital presenting the Kurathi (gypsy) with the typical action of spotting and removing the lice from a fellow gypsy's hair, and squashing them between two thumb nails. On questioning she said, "That is the gypsy." Her lectures have often pointed out that lokadharmi has its place in the stylized idiom too, and one should know that. As one of the greatest of scholars, one does not question the veracity of what she says, with a sense of responsibility. And dance theatre does accept theatre along with dance. But my question pertains to a Varnam which is the quintessential acme of a Margam presentation, with its own strict discipline. Here, how much of the simian mannerisms, from the monkey scratching to the typical monkey facial pout, and walking, even in a jati, as part of the choreography can one have? Is there no difference between one who dons a role in a dance drama, wherein he becomes the character, and the dancer in a Margam, wherein there is that distance between the dancer persona and that which he is to represent through the stylized language of movement and mudras? Is it ultimately a very personal choice? One would like to hear viewpoints. ANANDITA NARAYANAN IS A FEATHER IN THE GURU'S CAP Photos: Innee Singh  Anandita Narayanan The evening at the Triveni auditorium was titled Anavarna (Exploring the layers) presenting dancer Anandita Narayanan, a disciple of Bharatanatyam Guru Geeta Chandran. Expecting another of the well trained students of this teacher, one was totally unprepared for the mature performance of one, who, as the saying goes, has arrived - namely has graduated from locating the dance within her, to the point when she is beginning to discover herself in the dance - the latter a long process which in many cases, never happens. After the "Siddhi Vinayakam" prayer song, the Alarippu in Sankeerna Jati straight away brought to the fore, the dancer's confident rhythmic ability. The Kambhoji Varnam "Sarojakshiro," a Tanjore Quartet composition, is framed round the usual Nayika plaint addressed to the 'lotus eyed sakhi', persuading her to carry her urgent message of love to Lord Brihadeeswara, at this ('iti samayamu'), the right time when Nature in all her bloom is sporting scenes of coupling creatures. The way the involved dancer spun image on image, totally absorbed in the depiction, with no need for any glance for reference to the teacher, proved her supreme control over what she was doing. By the time she came to the charanam to complain of the Naaraja Baanam (love darts of Manmatha) aggravating the pangs of love, she was in a world of her own. As for the supporting musicians led by Geeta Chandran's nattuvangam (in a class of its own), with K. Venkateshwaran's vocal chords in soaring delight, with G. Raghavendra's violin, Manohar Balatchandirane's (jatis contributed by him and Lalgudi Ganesh) spirited mridangam and the delightful Varun Rajashekharan's ghatam, it was difficult to say who was being inspired by whom. The cumulative effect was very striking.  Anandita Narayanan From Shiva adoration, the dancer went on to Tirumangai Alwar's Pasuram extolling Vishnu. Ascribed by scholars to a period roughly between 731 CE to 796 CE to the time of Nandivarman II, the Pallava King, Tirumangai Alwar, the last of the twelve Alvar saints, had a very colourful past. Born to the Kallar community, this son of a military commander was also a robber before he became a commander himself under the Cholas, governing a small area Ali Nade before he converted to Vaishnavism influenced by his wife who insisted on his conversion. Rising to be one of the greatest bhaktas of Vishnu, he visited 85 of the revered shrines dedicated to Vishnu in South India. Against penance, advocating only the Bhakti Marg, he penned 1351 of the 4000 Pasurams of the great Vaishnavite text Divya Prabandham. Selecting verses 1018 to 1021 of Tirumangai Alwar, set in four different ragas by singer Venkateshwaran, Anandita presented her own dance interpretation starting with images of Vishnu lying on his bed of the serpent couch, in the Ocean. After this, brief images of Krishna's childhood events of slaying of Poothana, and of his holding Mount Govardhana aloft saving the inhabitants from the rain deluge, and of Arjuna being treated to the Vishwaroopa on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, to the final scene of divine dance of the Gopis of Brindavan, it was a dancer filled with devotion. The bhakti underlying the homage came from within. This truly inspiring performance while proof of the dancer's hard work and involvement, for this critic, was a credit to the teacher, who while teaching and insisting on sticking to the traditional discipline, gives the student the freedom to grow as an artiste. Manodharma needs free space to evolve.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Please provide your name along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name in the blog will also be featured in the site. |