|   |

|   |

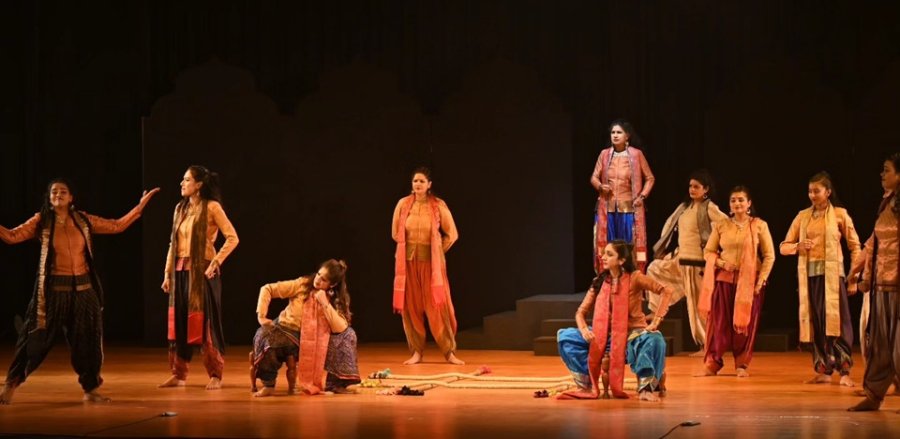

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Music Academy's annual dance delugePhotos courtesy: Madras Music AcademyJanuary 26, 2026 The words of Duke Orsino in Shakespeare's twelfth Night, '...Music and more of it, so that the appetite may sicken and so die' substituted by the word Dance, would well express Music Academy's 19th Dance Festival! How else does one describe thirty-two performances in seven days? Taking in sixteen of them with a colleague taking in the other half, was enough to leave one bleary eyed.  Natya Sankalpa ensemble It was a good way to start with a group expression, Karuna Kavya conceived and choreographed by Urmila Sathyanarayanan, the latest dancer to merit Music Academy's Nritya Kalanidhi award. Presented by students of her institution Natya Sankalpa started in 1996, Karuna Kavya turned out to be a slick production based, very imaginatively, on legends behind poetic masterpieces of devotional literature, composed in myriad ways-- through visions, divine interventions, miracles and what have you - beyond the pale of man's daily existence. Recited with fervour by myriad devotees to this day, how many ever think of the origin of these compositions or of the circumstances which led to this sacred literature, composed by compassionate, humble people who asked for nothing for themselves? Urmila's work stood out for its production values, starting with the musical composition by violinist Embar Kannan, with Srikanth Gopalakrishnan, K.P. Shravan and Krithika for vocal support and with Dr. G.V. Guru Bhardwaj, S. Ganapati Venkata Subrai, Bhavani Sankar, Shruti Sagar, Malai Karthikeyan, Saikripa Prasanna, on mridangam, tabla, veena, flute, nadaswaram and nattuvangam respectively - the entire effort making for an inspirational take- off point. Urmila's choreography, given its well-honed feel for utilizing stage space, along with a well-trained set of dancers, where even the youngest who seemed about five years old, acquitting herself with credit, left little to be desired. Starting with a Shanti slokam, dancers facing and addressing different directions, the story begins with an 8th century Lakshmi Stotram, the composer being boy Shankara. Having already taken to sanyasa - he was begging for alms - fruitlessly it would seem, until a destitute brahmin woman throws him a gooseberry, which the youngster accepts gracefully, and in gratitude for her graciousness, recites the Kanakadhara Stotram in praise of Goddess Lakshmi, upon which a shower of golden gooseberries rain down on the woman to lift her out of poverty! Next was the popular Alamelumanga Shathakam composed by Annamacharya (1404 -1503), whose fifteenth century compositions inscribed on copper plates were discovered hidden in the Venkateshwara temple only about 1922. Abhirama Bhattadri's Abhirami Andadi composed by a Hindu saint Subramanya of Tirukkadaiyur, came next. Living in a modest temple devoted to Amritaghateshwar and consort Abhirami, his deep devotion for the Goddess and respect for every woman (viewed as an incarnation of Abhirami) was deemed lunacy. Seeing the full moon in the Goddess's bright face, Bhattadri was condemned to die by the King Sarfoji, for seeing and mentioning Paurnami, where there was only darkness. He was saved by the Goddess throwing her earring into the sky to make the dark night shine like a full moon night. With so many independent groups on stage - comprising Abhirami on one side, Subramanya on the other and Sarfoji too in view, it was amazing to see how different groups, without distracting, were so positioned, as to appear knitted as part of one story And the costumes were so completely in tune with the times and the part of India the scene belonged to. For example, was the Maharashtrian flavour of the Jana Bai episode, with the Abhang tunes playing the varkari tradition Janabai belonged to (1270-1350) while she worked as a maid of the family of Sant Namdev - for this critic the entire segment with the dancers in typical Maharashtrian drape in their costumes, had a very authentic feel. Next Jayadeva's Gita Govinda took one to Odisha of 12th century, with the enactment of a scene when Lord Jagannath himself, as believed, secretly entered Jayadeva's house, to pen the line smaragara lakhandanam mama shirasi mandalam, dehi padapallava mudaaram for the ashtapadi “Vadasi yadi kinchitapi” which Jayadeva was agonizing on, unable to think of a relevant line assuaging Radha's anguish at Krishna's neglect. Next came Swami Tulasidas' forty chaupahis in praise of Lord Hanuman in Hanuman Chalisa, believed to have been composed at Kashi's Sankatmochana Hanuman temple. The last scene was built round Shankara's Manisha Panchakam, expanding on Advaita's core truth of non-duality of Self and Brahman. The episodic background showed Shankara asking a Chandala (Lord Shiva himself) to move, with the latter asking whether He moved or Consciousness moved, to make Shankara realize that Brahman was one. Costumes were excellent and knitting these episodes together, while preserving a feel of continuity in the production, was praiseworthy. KATHAK SANS SPARKLE  Monisa Nayak's group The group productions for the festival were on the whole a very mixed lot. One misses the genius of Maharaji and the aesthetics of Kumudini Lakhia, and it would seem as if Kathak dancers have lost the imagination required for group productions. Kathak Dhaara visualized by Monisa Nayak, a post graduate of Delhi's Kathak Kendra and disciple of Rajendra Gangani, while imaginative in concept, proved to be a rather tame event. Built round the idea of Kathak dance as a flowing stream, the start was with an invocation to sun god Mithra with the awakening of daylight, with the stream travelling through the day gathering energy (symbolized in the nritta ad-forms pertaining to the Jaipur gharana in Teental and Adha Chautal). Flowing on, its vitality softens towards the evening, depicted through the Tirbat in raga Kalavati set to a traditional bandish, Saanj suhai ati mana bhayi built round the nayika, who after sringar, sets out as the Abhisarika. This was followed by a Narayan Prasad thumri, Aiso hathilo chail maga, depicting the Gopis/Krishna Ched Chad, with the typical chaal or gait balancing the matkas (with Kavits expressing the Matki Phodi). The now mellow dance flow moved on to the popular devotional Stuti in raga Kalyan, Sri Ram Chandra Kripala Bhajaman with the finale in Bhairavi with a tarana Na Dir Dim Dim Dim in TeenTal-Drutlaya, by Monisa herself. Without live percussion, Kathak lacked that feel of immediacy in the dance, and the students, while technically correct, were not exceptionally evolved. With the foot mikes also not working for the first few minutes, the proceedings seemed lacking in energy. On the whole, in the midst of chakkars, the evolution of a dancer, who had been teaching in Delhi's Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, in an atmosphere which reverberates music and dance, was not felt in the performance. MORE EXTRAVAGANZA THAN DANCE  Sheela Unnikrishnan's group Moving on to Sheela Unnikrishnan's group offer of Ekadasa Vishnum, woven round the grandeur of the sacred Tirunangur Garuda Sevai festival, celebrated in the months of January and February, one wondered what this lavish docu-drama type of presentation with a mammoth troupe of 65 dancers, representing Sheela Unnikrishnan's Sridevi Nrithyalaya was doing in a prestigious dance festival. Characters strutting, resplendently clad as deities representing Vishnu and his avatars like Varaha or as Bhumi Devi, sporting a plethora of lavish crowns, masks, horns, feathers, and Vahanas like Garuda, added up to an extravaganza, school children would have reveled in. Supplementing the dance, were introductory visuals with temple outline and reference to the eleven sthala puranams of Vishnu's Divya Desams - namely the temples of Turuakkoodam, Tiruvaikkunta Vinnagaram, Tirutheir Ambalam, Tiruvenpurusottamam, Tirukkavalambadi, Thitu Devanarthogai, Tiruvallakkulam, Tirumanimadakkoil, Tirupartanpalli, Tiru Arimeya Vinnagaram, and Tiru Seonsei Koil. All that one remembers of this visual riot is of characters parading in and out - without the elementary dance aspect seeming to evolve at all, despite the elaborate music. One wonders what made Dr. Sheela Unnikrishnan, with fine students to her credit, decide on such a choice? WHITHER SHARMILA?  Sharmila Biswas group Sharmila Biswas, Artistic Director of Odissi Vision and Movement Centre, Kolkata, after a couple of delightfully conceived recent productions, for the Konark Festival and Chennai's Dance for Dance Festival curated by Malavika Sarukkai respectively, visualized for the Academy Festival, an Odissi work which seemed to evoke mixed reactions. Titled Murta Maheswar, it was described as 'A Dance Theatre Musical show - about environmental ethics and conservation - connecting Passive and Active energies, the Inanimate and Animate - comprising three short episodes of Dance-Theatre-Music.' Binding environmental concerns with Shiva, who as Panchakshara represents all cosmic activity was fine, for the Cosmos is his theatre with the five cardinal elements of Earth, Water, Sky, Fire and Air. And as Pashupathinath, he presides over the animal world as much as the human, for the word pashu stands for a human being too. As Shiva/Shakti, he also represents opposite and contrary energies coming together in unity. Maithun, the first part of the production representing union, was as much in the rain drenching Prithvi or Mother Earth to produce new life, as in the coupling of male and female in animals and humans. But the representation of the animal world in the production seemed endless - and audiences hoping for Shiva/Shakti union being depicted by Odissi resembling Kelucharan Mohapatra's Ardhanariswar, were treated to a surfeit of the animal spirits, though portrayed by well-trained bodies. With the next scene Aranyak, the work still remained in the crawling, creeping, swimming, leaping animal world. The last part of Dhwani / Pratidhwani, woven round percussion instruments, (for after all it is Shiva's damaru representing sound symbolizing the awakening of life in the cosmos), the well- trained dancers went into an improvised rhythm session to a language of Odissi rhythmic syllables, and percussion sounds. A heartening sight, demonstrating fellow feeling among the dance community, was veteran Bharatanatyam dancer Rama Vaidyanathan's daughter Sannidhi, stepping in to provide mridangam rhythm. A measure of Odissi as envisaged, would seem to have been ushered in, in the final segment. While a few in the audience expressed respect for a dancer's courage in thinking of a work taking Odissi away from its 'cloying sweetness', with some others praising the sheer exuberance of raw animal energy in the dancers of the presentation, most missed the absence of the usual tailored, Odissi dance. And Sharmila would seem to have entered a phase of no raga music. Of course, the world of Bhubaneswar Misras and of Raghunath Panigrahis, is over. But one would be sad if Odissi were always to be without the melody of singing and raga music. Sharmila Biswas' choreographic imagination has taken a new route. As one who respects artistic freedom, one realizes that varying audience responses to new ventures are a part of this journey. HIGH DECIBEL THEME NEEDED STRONGER KATHAK  Devaniya group Chennai based Kathak dancer Jigyasa Giri, trained under Benares gharana guru Krishna Kumar Dharwar, and later Bangalore's Maya Rao (representing Lucknow gharana of Shambhu Maharaj), in what was termed 'an English theatrical production in Kathak,' presented the work DIIS - Dancing Illusions in Stillness - rendered by students of her institution Devaniya in Chennai. Built round the central part of the story of the Mahabharata, surrounding the dice play in the Kaurava court, Draupadi's humiliation followed by the Kurukshetra war, and the essence of the timeless wisdom of the Bhagavat Gita as taught by Sri Krishna to Arjuna, one had the unusual experience of witnessing all of 18 male roles with one female role of Draupadi - played by 19 female dancers! The theme, treated innumerable times by Kathak dancers, is hardly new. But having this hour and fifteen minute production as 'an English theatrical presentation in Kathak' (with a continuous running voice commentary comprising even the dialogues), through five scenes based on a 'canvas of poetry, dialogues and dance' with pre-recorded music, was, one feels, rather misguided. With so many characters crowding the stage in costumes comprising salwar and a short kurta each in a different colour, moving with flailing hands as gestural response to the commentary and an occasional interjected foot stomping (not registering all the syllables of a rhythmic phrase) with a chakkar or two completing the phase, made for very scanty and rudimentary Kathak - which, in full flow, was never seen. Having seen some of Jigyasa's work, which has a lyrical quality, what was seen here was totally inadequate. Without the added body and throb of live music and percussion, (not easy in Chennai but available in Bangalore) attempting such work was ambitious beyond belief. DELECTABLE YAKSHAGANA  Yakshagana group A welcome diversion from the studied world of classical dances, with a blend of music, theatre and impromptu spoken dialogue in Kannada was the Badagathittu Northern school of Yakshagana from South Kanara, portraying the episode of Dakshayajna, choreographed and directed by Keremene Shivananda Hegde of Idagunji Mahaganapati Yakshagana Mandali. Built round the veera, raudra, arbhuta, bhayanaka rasas described in the classical texts, Keremene Shivananda mentioned in the opening announcement that Yakshagana had been accorded the recognition of being part of India's 'intangible cultural heritage'. Sadly, the audience in the Music Academy Hall was not very large, but those who stayed back, for the last show of the evening, enjoyed the vibrant presentation. Not invited to the Mahayaga/Mahasabha conducted by the gods with Shiva presiding, vengeful Prajapati Daksha holds a mammoth Yagna of his own, at his kingdom of Prachina Barhi - inviting the whole world, barring Shiva, his son-in-law. In anguish at husband Shiva not being invited by her father, Dakshayani throws herself into the Yagna Kund. The start with the stentorian voice of the Bhagavatha whose voice production (used to singing in open fields with no mikes, to large audiences) stands in a class of its own - belting out ragas like Kambodi, Mohanam, Shivaranjani et al, without needless brigas, to the accompaniment of the maddale percussion, gave the entire proceedings a robust quality matched by the dance - both energetic and graceful, punctuated by leaps and mandi adavus, with a rich use of facial expressions and hastas. The start was with a salutation to Ganesha, with a representation of the elephant face appearing from behind, in the center of the curtain, held aloft by two hands stationed on either side of the performance area, before the Prasanga with various characters forming the Mummela took over. Turned out in dhotis tied 'kachhe fashion', elaborate hairdo (mundas), and jewellery adorned with crowns, and body covered with ornaments like Bhujakeerthi, Yedekattu, the shoulders adorned with Tolubahu - plus the impromptu dialogue in Kannada - which in a tone of intimacy and informality as in daily human life, was centered round exchanges between the gods, as between Shiva and Parvati. Shiva is described in sarcasm by father-in-law Daksha, as Tandava Natyavanu, and also as Smashaneshwar Kreede! The actors enter with Oddologa (ceremonial entrance of characters) with tailored dance movements in energetic rhythm, rendered to the accompaniment of the Himmela comprising Chenda Maddale and Bhagavatha singing. In this impromptu/stylized combination, the enactment kept the audience fully entertained with Shivananda Hegde himself in the role of Shiva. NRITYAGRAM FINALE  Nrityagram ensemble Music Academy has made a ritual of Nrityagram's Odissi as the finale for bringing down the curtain to this annual festival. This institution, through fluctuating fortunes, has managed to get together an ensemble under Surupa Sen's lead, comprising Pavithra Reddy, Anoushka Rahman, Daquil Mirala, Namaha Mazoomdar, Srikalyani Adkoli, Aishani Dash and Adithya V.S . The distinctive feature is of an all-Indian group of dancers with this representation from different parts of India, with only one from Odisha - which gives an indication of how Odissi, like Bharatanatyam and Kathak, has absorbed and been enriched by so many sensibilities, as a classical form. The start to the performance was with an involved Oriya composition as an invocation. The Dasavatara presentation set to Ektaali rhythm, composed by mardal expert Dhaneswar Swain along with Surupa Sen, was based on the poetic narrative from the Gita Govind, Pralaya payodhi jale dhritavaanasi vedam. Choreographed by Surupa, who as Sutradhar also recited the relevant poetry at the start of every manifestation of the saviour, the dance content was entirely based on rhythmic syllables. While there was a musical quality to the rhythmic language of syllables, doing away with the melodic rendition of the verses, showed how evocative the syllabic recitation could be. The Dashavatara Ashtapadi, as early as round the 11th century when the Gita Govinda is believed to have been composed, has been interpreted by scholars as epitomizing the story of life on earth with evolution of Man - better than any Darwin theory. Life first appears in water as fish (Matsya) and then in water with ability to move on land too as Kurma, followed by life on land as Varaha, the boar, holding aloft Mother Earth in danger of sinking in the seas. Then comes Narasimha as half man and half animal. Full-fledged man first appears in dwarf form as Vamana, after which is the axe wielder Parasurama, intent on destroying warriors, followed by bowman Rama, who lives by dharma in life and war. Next is the soil tiller Balarama and finally comes the evolved messenger of peace and love as Buddha, concluding with the belief that to quell adharma by re-establishing the power of good, the saviour as Kalki will arrive. Following this opening, the accent on sringar, was woven round the animal world (which seems to be the dominant choreographic concern of some other Odissi veterans of the day too). First came the Mayura Sringar in Ektali, wherein, some of the bodily bends and positions spoke of rare creativity and observation of nature on the part of the choreographer Surupa Sen. While there was no composed music as such, the effects, with Mayur like calls, produced, with the mardala effects by Rohan Dahale (trained under late Banamali Das, a master percussionist), with violin and flute by Anup Kulthe and Parsuram Das, with Jatin Sahu's (gradate from the Music college in Odisha) music, vocalization of sounds and harmonium, revealed the kind of rhythmic/musical, percussive ensemble, resembling sounds fashioned by those living close to nature - which one feels is natural for Nrityagram, situated so far from the cacophony of sounds of the madding crowd. It also explains Surupa's uncanny feel for the movement of the animals and how they can be made to fit into the stylized movement idiom of Odissi. That closeness to nature continued in the next sringar scene between elephants. For this writer it seemed a telepathic coincidence that earlier in the festival, a Bharatanatyam veteran Priyadarsini Govind had also woven a love composition in Tamil, like a padam, round a male elephant as the Nayaka, feeling hesitant about rejoining his mate, after being disfigured by the injuries of war depriving him of his proud tusk, and damaging a foot nail. One must, again commend the imaginative dance movements. The finale was Memories, based on fleeting images from an eventful past, an abstract creation titled smritiranga. This recapture of a varied past - of arrivals, of departures, comprising memories of expanding dance group and of a thinning ensemble (some of the incidents are well known to the public too) of joy, of sorrow and disappointment, reflected in the movement visualization, with music one cannot pin down to specific raga designs. Interesting, though one felt the item was over extended leading to audience attention spans diminishing. Surroundings colour the mind with images amidst which one grows and evolves. It is interesting to watch the artistic growth of Surupa Sen, living for years now, with only the dance and nature as companions - of how choreographic images evolve, when living far from urban distractions! More muscle to her artistic imagination! But as one who loves Odissi music, I hope it remains an essential part of the dance.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Please provide your name along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name in the blog will also be featured in the site. |