|   |

|   |

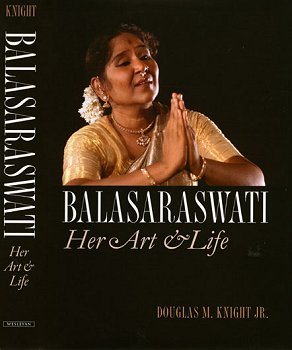

Dance readings and musings Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life - Ragothaman Yennamalli e-mail: ragothaman@gmail.com July 26, 2010  In

February 2010, I got to know about the scheduled release of Balasaraswati's

biography by her son-in-law Douglas Knight. When I finally got my copy

after a long wait, I finished reading it at a feverish pace. 2010 has started

off as a good year for Indian dancers with the biographies of Rukmini Devi

Arundale by Leela Samson and that of Balasaraswati's by Douglas Knight

being released one after the other. I hope there will be more about other

gurus in the future. In

February 2010, I got to know about the scheduled release of Balasaraswati's

biography by her son-in-law Douglas Knight. When I finally got my copy

after a long wait, I finished reading it at a feverish pace. 2010 has started

off as a good year for Indian dancers with the biographies of Rukmini Devi

Arundale by Leela Samson and that of Balasaraswati's by Douglas Knight

being released one after the other. I hope there will be more about other

gurus in the future.Balasaraswati hailed from a devadasi family and her knowledge on music and dance was deep and comprehensive. Initiated into dance by Mylapore Gauri Ammal and later mentored by Kandappa Pillai, she proved to be a versatile dancer in her community. It is interesting to know that she was fully aware of the social context in which her dance career was launched. She was in an era in which royal patronage to performing arts had been replaced by a new breed of rasikas. Today, a student of Bharatanatyam is introduced to Balasaraswati through the Sringararasa controversy rather than her contribution to the art form. The book presents her opinion on this matter clearly. Rather than taking a side, I would recommend the reader to read her perspectives and judge for themselves. This write-up does not pay more attention on this issue, rather it is on her art and life. The book is filled with interesting anecdotes, quotes by Balasaraswati in her interviews, the experiences shared with the author by people who interacted with her, and many other tidbits that make it an amusing and insightful read. To this day, some of the Padams and Javalis are considered as their family heirlooms. To her credit, she was the only dancer to be conferred the Sangitha Kalanidhi title by Music Academy. The humor in a photo of Balasaraswati with MS Subbalakshmi taken in 1937 can only be relished by viewing it! Though trained as a soloist, she choreographed two dance dramas in her lifetime. Some facts about her and her family revealed by the book are quite informative. Like, her partner was the first finance minister of India! She choreographed on "Jana Gana Mana" much before it was adopted as our national anthem. Some of her concerts went on from 10pm to 3am! And concert performances were filed as income tax - a common practice among traditional dance families. The custom of seating musicians on the side stage, in level with the dancer, is attributed by many to have been initiated by Rukmini Devi Arundale. However, as per the book, this custom was started by Balasaraswati's guru, Kandappa Pillai, as a mark of respect towards Balasaraswati's mother Jayammal, who accompanied her for her concerts. However, the book fails to mention whether this custom was adopted by other dancers as a regular practice. Kandappa Pillai also introduced some radical changes in the dance form, most notably,the Teermanams, that attracted musicians to Balasaraswati's concerts. As evident from the book there was active communication and peer-review among the traditional dance families. Some snippets of such interactions are mentioned in Chapter 3. An interesting anecdote is of Mylapore Gauri Ammal's response to another devadasi named Muthu Kannammal - quoting from the book, she comments that "her abhinaya could be a little vulgar." Certain passages provide the traditional dance family's perspective to the efforts of E Krishna Iyer and his peers, in introducing changes to Bharatanatyam. They were clearly viewed as a threat to their source of income. Understandably, with the changing social situation, traditional dance families did not see institutionalized learning as reviving or rescuing the art form. Balasaraswati herself was of the strong opinion that the art form did not need revival. I feel that only a true practitioner like Balasaraswati could make such an opinion. Traditional dance families were not particular about costume and presentation styles. For them, the execution of the art was of primary importance rather than the appearance of the dancer. Hence, they did not support costume changes and considered Kritis unsuitable! In their opinion, such changes lowered the art form. At the same time, quoting from the book, Guru Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai agreed that "there is bound to be change and new ideas. But these can be called by a different name and not brought under the name of Bharatanatya." In my opinion, changes within the accepted format were most welcome but not otherwise. I feel that few statements in the book should be taken at face value as they are not supported by evidence. For example, "Their (Rukmini Devi Arundale and Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai) relationship ended with this event" (the event referring to Rukmini Devi's performance at Theosophical Society). Jayammal, Balasaraswati's mother, used to accompany her concerts as a vocalist. The author chalks out vividly with multiple instances, the delicately balanced mother-daughter, dancer-vocalist relationship strained by the daughter's rise to fame. One such instance had led Kalki Krishnamurthy to comment in his review about the "lack of cooperation" between the two during the performance. Speaking of her guru Kandappa Pillai, he acknowledged Balasaraswati as his dear disciple only once, for the first and last time on his deathbed! Balasaraswati was discouraged from listening to any comments or praise by her audience following her performance. She only had to listen to her inner voice to assess whether she performed with pure devotion and dedication. This personal connectedness is recounted on her 1960 Music Academy performance where she couldn't feel it while performing the shabdam "Devadevanam." Balasaraswati was extremely disappointed about that particular performance. After reading this passage, I felt that this is very true to every dancer. Until and unless they felt personally connected to the performance, the radiation from the dancer to the audience is not felt at all. She was indifferent to critics throughout her career who complained about her being either too young or too old, either too thin or too fat. In her own words, she didn't dance for fame or for others. She danced because she liked to dance. Alas, such personalities are rare in these times. Balasaraswati was well-known for her abhinaya. Her quote, "Dignified restraint is the hallmark of abhinaya…The divine is divine only because of its suggestive, subtle quality," proves her merit. Quoting from the book: "When asked why she thought there was deterioration in standards and expectations of art, she suggested it was the result of the fuss generated around young dancers, the pressures to perform at an early debut, and the indiscriminate acclaim given to young dancers before they had found their feet." This she said in 1957! Aren't these words so relevant even in 2010? Many such quotes throughout the book ascertain the fact that she was a purist to the core. She was very fond of children and taught them with care and affection. The fact that she understood body kinetics is supported by instances recounted in the book. At the peak of her career, technology had advanced to a stage where her life could have been well documented. Unfortunately though, very few videos of her were recorded (3 are available) for future generations to understand and learn from her art form. Widely acclaimed director Satyajit Ray's recording of her rendering "Krishna nee begane baro" with the Mahabalipuram beach as a backdrop, does not do justice to her skill (Youtube link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axuq7ncvjYE). It is really a wonder why he did not do extensive recording of her art even at the negative critical response received after the advance screening. The doyens of Bharatanatyam did not realize the significance of documenting their work for posterity. Thanks to the painstaking documentation by her family, this book will remain as a source of inspiration for current and future Bharatanatyam dancers, who wish to understand Balasaraswati, her life, her art, and her philosophy. Condensing 80 years into 252 pages is not easy and it cannot do justice to a lifetime dedicated to an art form. However, Douglas Knight's effort in this direction to popularize Balasaraswati and her art is highly commendable. In my personal experience, till date her contribution to Bharatanatyam was unavailable in detail. In this regard, I feel this is a priceless resource that recounts important facets of her life. One gets to understand her life more clearly and also about the people who shaped her life and dance career. While reading, one cannot escape the feeling of sharing a personal space with Balasaraswati. A must read for those who are interested in Bharatanatyam and its history. The book erroneously mentions Ganapati as "the benevolent form of Siva as the elephant god." Ragothaman Yennamalli is a student of Bharatanatyam, learning from Guru Vijayalakshmi Ramanan, New Delhi. This is his first article for narthaki.com. He would like to thank Anupama Bhat for her motivation. |