|   |

|   |

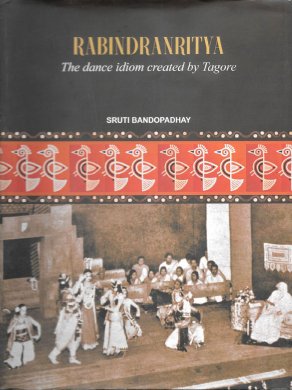

Tagore's Ethos of Dance - Dr. Utpal K Banerjee e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com September 25, 2019  Rabindranrityam: The Dance Idiom Created by Tagore By Sruti Bandopadhay Shubhi Publications, 479, Sector14, Gurugram 122001, Haryana, India Email: shubhipublications@yahoo.co.in 2019, 314 pages, Price Rs. 2995 ISBN 9910032282 Primarily a poet, but also a philosopher, a novelist, a lyricist, a painter and a man of letters, Rabindranath Tagore brought in a new sensibility in the dance scene in Bengal. An admirer of Indian classical dances as well as the myriad folk forms, Tagore sought to break the boundaries and evolve a new dance idiom. While retaining the essential "Indianness," he allowed to let it absorb classical and folk elements from all over the country as also such elements as Sri Lanka's Kandyan dance, Javanese and Balinese dance idioms that had enchanted him. A popular dance form gradually came out -- alongside his song tradition, known as Rabindrasangit -- that can truly be termed Rabindranritya (Tagore's dance). A major plus point of the present book is its detailed documentation on history, presentation and practice of Tagore's dance. The way contemporary press-clippings have been collected and collated fulfills a long-standing need of understanding the viewer appreciation. The book has seven chapters, where the gradual development of dance along with its essential elements has been discussed. The first three chapters - the beginning, the budding and the shaping - have extensively dealt with the history and development of Tagore's dance. He created two musical dramas early in life - Valmiki Pratibha (1881), Kal Mrigaya (1882) both on Ramayana themes and a pure musical, Mayar Khela (1888). For a recently Europe-returned Tagore, they seemed to follow respectively the post-Wagnerian style with a dramatic approach and pre-Wagnerian style without drama. Dance gestures were on a low key. He consciously used certain Irish tunes in his Gitinatya (musical drama) and followed Herbert Spencer's dictum in connecting emotions to speech. He had witnessed Manipuri dance in Agartala in 1899 heralding spring and Sharadotsav (Festival of Autumn, 1908) - penned for performance of his students - marked a new phase of Ritunatya (seasonal drama) with celebration of nature henceforth. In this play, Tagore danced in Baul style and the rest followed flying coloured cloths in the sky. Next, Phalguni (1915) had the theme of celebrating spring, as also overcoming the old age despair and fear of death. Basantotsav (1923) was followed by Barshamangal (1925) and then came Nataraja Riturangasala (1927). Tagore visited Java and Bali in 1927, followed by Rituranga when dance gestures became highly developed, as noted by Pratima Devi. Sundar (the Beautiful, 1929), many productions of Barshamangal and lastly Nabin (the New, 1931) were all in the same genre. In 1934, Burmese dancer Pwe, visited Jorasanko, Tagore's Kolkata abode. Pratima Devi played a key role in introducing and continuing dance practice among the girl students of Santiniketan. Natir Puja (The Worship of the Danseuse, 1926) in Manipuri dance form played a key role in bringing girls on the public stage for the first time, creating a cultural revolution. Mohiniyattam, and then Kathakali, became subjects at Santiniketan. Presentation aspects gained uniqueness through symbolic representation and colourful costumes and sets. Dance teachers from all over the world were invited to participate and education system became thoroughly innovative and holistic, marking a new beginning for the entire country. Nrityanatya (Dance dramas) marked another phase, with Shapmochan (the Redemption, 1933) and Tasher Desh (the Kingdom of Cards, 1934). While the redemption was hailed by the press as in the Greek sprit and design and Javanese in execution, the stultified card-kingdom and its breakdown was welcomed as thoroughly iconoclastic. They were landmark productions travelling all over the country and Southeast Asia. Chandalika (the Untouchable Girl, 1938) was the third path-breaking dance drama, looking hard at the social stigma and stipulations. Then came the dance drama Chitrangada (1936), hailing triumph of femininity, where the beautiful heroine danced in Manipuri technique, while other characters like Arjuna had Kathakali and Bharatanatyam blended, apart from some folk dances. Chandalika was assessed as a blending of ballet and opera, but also used the sensitiveness of Manipuri enlivened by the hasta usage of the South Indian styles. In essence, Chandalika was a revival of the ancient Indian form. Shyama (1939) was the other dance-drama, now based on a Buddhist parable where the dancer-courtesan's love for a foreigner goes awry. Kathakali was used for the hero (Kelu Nair), Manipuri for the heroine (Nandita), and Bharatanatyam for Uttiya (Mrinalini), in the beginning. Lastly, efforts to transform Mayar Khela into dance-drama was not too fruitful. This highly encapsulated summary covers the first three chapters, followed by two very useful and innovative chapters on the accompaniments and accessories, with the former covering the musical support and the latter upholding the beautiful Tagore culture of costumes and set-designs. The penultimate chapter on the personalities who carried on Tagore's works and choreography is a little too ambitious and largely Bengal-centric. An important omission is Dr. Ananda Gupta (1968- ), a Dakshinee product now in London, running Dakshinayan there, with highly successful productions of Shapmochan, Shyama and Chandalika, touring both sides of the Atlantic. But the most glaring omission is guru Valmiki Banerjee (1926- ), a Guru Gopinath student and director of the renowned Delhi Ballet Group, having crossed 70 years of dedicated Tagore's dance. He propounded and propagated Rabindranatyam, firmly believing that Tagore's dance thoughts are entirely in consonance with the Natyashastra. 'Rabindranatyam,' his English treatise on the subject, published by Rasavrunda in association with Raas Indian Art Foundation, Mysore in 2011 has been well-received and is the fruit of his long research on the subject for over four decades. The final chapter of the present book is a useful take on Tagore's pedagogy. An aspect not touched at all in the book is Tagore's oeuvre of more than two dozen colourful paintings on dance visualization, executed in the last decade of his life while he was creating his dance-dramas. This aspect is fully covered in this critic's earlier comprehensive book, 'Tagore's Mystique of Dance' (Neogi Books, New Delhi, 2011), along with many other aspects not covered in the present book. Indeed, it would appear strange that her blurb mentions, "After more than ninety years of practice, a comprehensive book on Rabindranritya is yet to be seen..." , when she herself was instrumental in making this critic's seminal work a prescribed text for the Graduate and Postgraduate studies in dance at Vishwa Bharati nine years ago! The present book is, nevertheless, a very useful tome for micro-level research in Tagore's dance practice, carried out with painstaking documentation and thorough investigation for which all credit is due. The publishers have done a wonderful job of the book-design and largely four-colour printing of the images. Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comment Unless you wish to remain anonymous, please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |