|   |

|   |

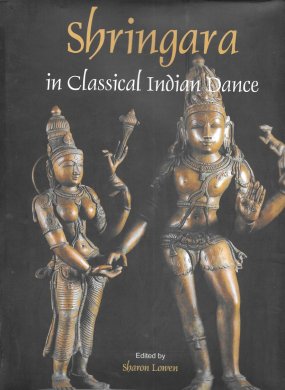

From amour to worship - Dr. Utpal K Banerjee e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com January 13, 2021  Shringara: in Classical Indian Dance Ed. By Sharon Lowen Shubhi Publications Gurugram, India E mail: shubhipublications@yahoo.co.in Rs. 2405, 2021 ISBN: 9788182903 647 At the outset, one would compliment the editor and the publishers for a beautifully produced book in 'coffee table' format,with an elegant design and ample color photographs of India's well-known dancers, most of whom have generously contributed to the theme that appears to be dear to their heart. The result has been a satisfying work one would love to cherish! Way back in 1998, while on a lecture spree in the Latin Americas on Indian art and culture, this critic was hosted at home by Dr. Victor Bentata, a very eminent man of letters, in the capital city of Caracas, while in east Venezuela. Taking this critic round the sumptuously equipped library in his hill-top mansion - more like a mini fortress - Dr. Bentata confided that India's ancient culture fascinated him no end and he had, in fact, a huge collection of tomes on the subject. Ruminating on the rich temple sculpture of our land, he presciently remarked, "The elegant, erotic reliefs and grottos - mostly of dancers -- sculpted on most of the temples' exterior walls were, according to me, meant to titillate and expurgate the viewers of their baser emotions. There have never been any amorous sculpture on the temples' inner facades, because by the time of their entry, the visitors were expected to be denuded of their animal instincts and worthy of the interior's holy presence." It was an interesting exercise to look at Shringara, the book under review, using the touchstone conceived by the scholar on the other side of the globe. The "Introduction" by Lakshmi Vishwanathan rightly sets the ground by quoting Natya Shastra's listing of all the eight rasas, from Shringara (erotic) to Adbhutam (marvelous), to which the later scholars added Shantam (peaceful). Shringara was then elaborated into Sambhoga (love in union) and Vipralambha (love in separation), both capable of a multitude of delicate expressions. Lakshmi eventually surmises that our dancers' trump card has been the concept of Shringara Bhakti, with all longings even expressed with explicit physical allusions, interpreted as love towards the divine - the proverbial Jivatma (human soul) yearning for the Paramatma (the supreme being). She concludes, "Classical dances take this route to tell the world" to depict Shringara. This unified view flies directly against the binary interpretation of India's sculptural heritage, held by scholars like Dr.Bentata! Looking further, Kamalini Dutt, with her vast experience of recording for Indian television, performances of almost all the stalwarts in the field of music and dance over four decades, points out that even the male bhakta seers, like all the Alwars (Vaishnava poets) and many Nayanmars (Shaiva poets) have taken the Nayika bhava to express passion to unite with the Nayaka that is Paramatma. These were in contrast to the non-religious Sangam poems comprising Akam (with innermost feelings of love) and Puram (about valor, victory and war). Later on, from Kuravanjis to varnams, padams and javalis, Telugu and Tamil lyrics swung between the mortal and the spiritual worlds. She also delineates how the two aspects of Shringara -Vipralamha and Sambhoga -- are linked in various devotional ways. Prof. Anuradha Jonnalagadda, a dedicated academician and student of the maestro Vempati Chinna Satyam, is of the view that Kuchipudi is deeply influenced by Bhakti movement and various stories of Vishnu as Krishna led to its treating Shringara in the form of Madhura Bhakti. Dr. Anupama Kylash, a reputed scholar and practitioner of Vilasini Natyam, avers that although there has always been an argument on the superiority of Shringara over Bhakti as a rasa, most rhetoricians of yore found a place of Bhakti under the components of Shringara. The lines between human passion and divine love were found to be completely blurred with the advents of Jayadeva, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and the cult of Radha-Krishna leela. Bharati Shivaji, a renowned exponent of Mohiniattam, holds that Shringara is the main sentiment that makes the mood for the dance, with divine grace as the motif. Dr. Anwesa Mahanta, a noted Sattriya dancer, is firmly of the view that Parama Prema Rupa of the supreme divinity, introduced in the Rig Veda, epitomizes Bhakti Shringara in her Sattriya dance tradition. Further, she emphasizes that Sattriya dance is based on the corpus of Bhakti components of Shankaradeva, Madhavadeva and the subsequent apostles who were the fount heads of the Bhakti movement in Assam. The constant shuffle between human and divine in the Bhakta creates the duality of Aakar (form) and Nirakar (formless) and govern the sentiment. Dr. Shovana Narayan, a celebrated exponent of Kathak dance, avers that the term 'Shringara' ranges from love filled devotion to adornments, to the beautiful emotion of friendship, to the emotion exuded through maternal love, to the joy expressed through a child's pranks or the adolescents' playfulness, to the various hues of emotions when in love that oscillates from hope, anxiety and in fulfillment (Samyog) and paradoxically to the love filled pain of separation (Viyog). Finally, the editor Sharon Lowen, a noted dancer-scholar herself, also argues that Shringara is the closest metaphor to an understanding of divine love in Odissi dance. The location of dance performance shifted from temple (in earlier times) to theatrical space (as at present) and artistes choose to create an imaginary sacred place. Thus, on the whole, the sum of opinions of the classical dancers writing in this tome, seem to be overwhelmingly against the tenets of scholars like Dr. Bentata, with very little scope of treating 'love' in its duality of 'sacred' and 'profane'. One wonders if there could be a further dialogue on this duality. The other interesting point about the book is that no contributor, other than the sole exception of Shovana Narayan, has considered the other important classical aspect of Shringara - adornment of the body. Indeed, this critic recalls having presented the well-known Kuchipudi dancer Swapna Sundari in Indian Doordarshan in 1974, under the aegis of its distinguished producer Sai Paranjape for a half-hour item Shodasha Shringara. This was telecast as part of Sai's popular weekly programme TV Folio every Tuesday. Swapna exquisitely demonstrated the sixteen Shringaras for head, for face and for torso in three distinct segments. The entire programme was illustrated for each of the three segments, backed by rich sculptural figures and paintings lent by National Museum in Delhi, from their rich archives under the supervision of its celebrated director, Dr. C. Sivaramamurti. Incidentally, the programme's contents were initially suggested by Swapna herself to this critic. Perhaps the editor of the present book could keep this aspect in view for future editions of an otherwise excellently done hand-book on an important subject in Indian dramaturgy and aesthetics.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comment Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous / blog profile to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |