|   |

|   |

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com Death and Resurrection April 18, 2018 In the Jharkhand state, Jharia is famous for its rich coal resources, used to make coke for steel making in India's gigantic steel plants. Jharia plays a very important role in the economy and development of Dhanbad City. Yet, about 70 fires have sprouted up at Jharia coal fields, which cover more than 100 square miles and mined since the late 1800s. The government has already spent money to move villages and settlements away from the mines, and those costs are forecast to reach an unbelievable $1 billion. Still, Jharia coal field has been burning underground for over a hundred years, as residents living across 250 sq km sit on a ticking time bomb... In Jharia and the contiguous rich coal belt of Raniganj in Bengal, there are also sporadic tracts of derelict mines, left out of officially designated coal mines, because they have gone out of commercially exploitable mining zone. While formal mining operations move out to elsewhere, there remains some potential to dig up the residual coal from under these left out areas. Vested interests sprout to illegally "mine" these tracts under dangerous conditions usually at night; and normally beyond the pale of law-and-order authorities or even in collusion. The hired labour used in these illegitimate operations naturally is not entitled to any protection against exploitation.

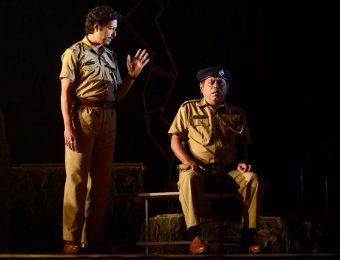

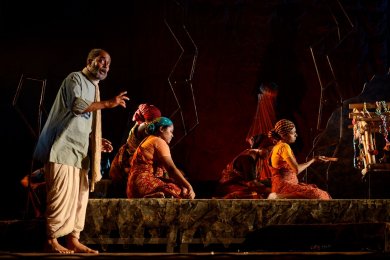

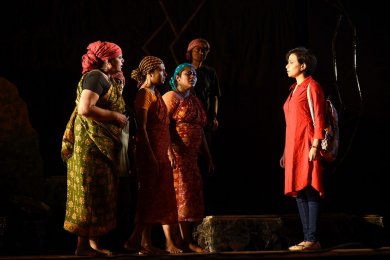

Punoruthhan presented by Sayak on March 28 in Kolkata, was based on the novel penned by Amar Mitra, which brought out the hard realities down the decades of unchallenged exploitation running rampant in what are known as Khadans (illegal spots of mining coal), owned and operated by coal mafias. Dramatized superbly by Chandan Sen and directed by the thespian Meghnad Bhattacharya, the play opened most imaginatively on a dimly illumined cyclorama where the scantily clad indigenous people are seen underground, lifting up costly coal and suddenly an ear wrenching accident takes place, causing explosions and deaths - - never to be acknowledged - inside those dangerously unsafe pits. Against the grain of normal events - when the dead bodies would never come back and their bereaved families would not receive any compensation from the greedy Khadan owners who control police and administration - Bharat Kuliya, a brave son of the soil, does decide to write a petition to the higher authorities alleging the cruel, unacknowledged death of three local laborers and seeking compensation. Immediately, the powers that be swing into action and Anindya, an arrogant additional SP (well enacted by Samiran Bhattacharya), not merely takes Bharat into custody, but also has him beaten to death in the lock-up. But the muted voice of conscience does gather a slim and unsure force in the honest OC Golak Bihari Kundu, in some police subordinates, in the doctor carrying out the post mortem - refusing to call Bharat's custodial death a "heart attack" and not signing on the dotted line - and surprisingly, in the DM's nubile daughter Bubun. At the outset, this slender axis of honesty seemingly loses out to Anindya pulling strings from his powerful father-in-law and even from the corridors of power in the nation's capital. The ins and outs of the 'power game' is well etched, a distracted Golak Bihari is hounded everywhere and the tribal hinterland of Rangamati seems gradually to feel the groundswell of opposition.

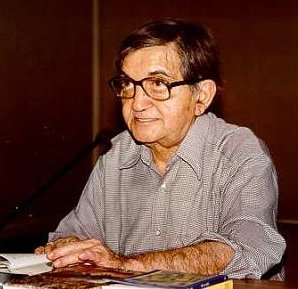

The play also stands on the strength of two other characters: first, Pawan (essayed well by Biswanath Roy), Bharat's bereaved father, who has lost everything by losing his only son, but who stands like a rock as the voice of collective conscience; and, second, the DM (donned by the director Meghnad himself), pressurized all around, whose Hamlet like vacillation - between 'to be' and 'not to be' truthful - - comes transparently through as often the land's true state of affair seen in its silent majority! It was a starkly realistic play which deserved kudos from the viewers and the final scene - with the symbolic rise of so many Bharats against a palpable iniquity - was like the proverbial rise of the phoenix from the ashes. Well done, Meghnad! Solitary Soliloquies Photos: Asim Pal  Nirmal Verma When Nirmal Verma (1923-2005), the flag-bearer of Nayi Kahaani movement in Hindi literature, pioneered his brand of brooding novels, stories, essays and travelogues, his penmanship was constantly seeking out the people who got left behind, having been first lured by the magnetic narratives of the city. Recipient of Jnanpith Award, Padma Bhushan and the Sahitya Akademi accolade, Verma developed a trenchant style, which used rich, realistic description as a mirror of the inner life. This was largely due to a very productive period of his literary life spent in the 1960s at the Oriental Institute in Prague, where he undertook direct translations of contemporary Czech writers, such as Milan Kundera, Bohumil Hrabal and Václav Havel into Hindi, much before their work became popular internationally. Czechoslovakia in the 1960s nurtured - during its brief lull of political and cultural freedom - - littérateurs like Milan Kundera, for whom Vertigo was something other than fear of falling; it was the voice of the emptiness below us which tempted and lured us; it was the desire to fall, against which, terrified, we defended ourselves. To Kundera, loneliness and solitude were the essential ingredients of life, but not quite the same way. Loneliness expressed the pain of being alone and solitude expressed the glory of being alone - - to go out with the setting sun on an empty beach was to truly embrace one's solitude. Then there was Bohumil Hrabal, whose book Too Loud a Solitude was a tender and funny story of Hant'a: a man who had lived in a Czech police state for 35 years, working as compactor of wastepaper and books. But when a new automatic press made his job redundant, there was only one thing he could do: go down with his ship. And also there was Václav Havel, for whom the tragedy of modern man was not that he knew less and less about the meaning of his own life, but that it bothered him less and less... Thoroughly soaking up the atmosphere of these three authors' sombre writings, Verma wrote his Teen Ekant - three gloomy outpourings - - which had been enacted memorably in Hindi by National School of Drama in Delhi. Out of the three one-act monologues, Ek Dhup Ka Tukra was staged very successfully in Bengali by Dolly Basu in Kolkata not too long ago. This was a story about a woman in a park, a very simple person that one encounters every day. Though she had a story to tell, she talked about her life and her perspective, questioning and wondering again about simple things that one easily overlooked. Her outpouring was addressed throughout to another person, sitting quietly at the other end of the same bench, but never uttering a single word. Towards the end, the man had left the place equally silently, bringing out the futility of the woman's entire narrative: even when one decides to open up one's soul, there is never another spirit to give credence... Amodito Roddur, showcased on April 7 by Pancham Vaidik in Kolkata and directed deftly by Debesh Chattopadhyay, was another Bengali version of Verma's introspective monologue - - but with the difference that the woman was seen addressing an imaginary person all along, there being none physically present on the park bench. This subtlety did cost an effort on the viewers' part to assume physicality of the absent stranger. More than that, it also strained the speaking woman - - enacted quite well by the veteran Arpita Ghosh - to keep her gaze focused at one static spot, to let spectators' attention also remain focused. Otherwise, it was a valiant chiaroscuro of one's humdrum life: loneliness, decrepitude, pain, debilitation, depression and even senility. Scenographically, the multiple benches in the park had - instead of the usual horizontal back rests - significantly, oblique planks, denoting tension and turmoil in life.

Verma's play was preceded by another, yet shorter monologue, penned and directed by Debesh, this time narrated quite creditably by Ankita Majhi. Her soliloquy took the audience through her own pen-portrait: fascination for acting in theatre, which made her boyfriend fall for her. Later, when she was due to go to NSD, Delhi, for a performance in which she was the protagonist, her father-in law died, but she was unable to stay back. The relations visibly cooled off and her husband told her to leave the acting profession. Her only alternative was simple: to pack up and leave. The scenography - again by Debesh - was quite striking: a set of dimly-lit rooms, set diagonally from each other, which she had to negotiate prior to her final departure: how many obstacles one has to face, to leave a settled life; how many miles one traverses before embracing uncertainty?  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |