|

|

|

|

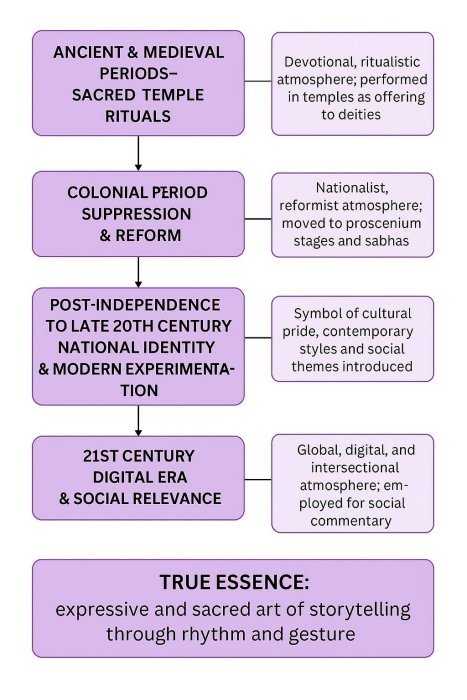

Cosmic cadence through proscenium time:Question and evolution of space across times in Bharatanatyam- Brinda Dhare-mail: brindadhar8@gmail.com July 13, 2025 ABSTRACT The term 'vivarta' refers to an illusory appearance of transfiguration. In a philosophical context, particularly within the Vedanta system, the doctrine of vivarta is utilized. The journey of space in Bharatanatyam, from temples to modern proscenium, incredibly moulds the spatial aspects through fusions, thus debunking the actuality of political Bharatanatyam, which has, however, remained constant for ages. Intersectional fusions then do more than blend contemporary politics with classical technique - they decolonize the very knowledge systems that uphold the dance's authority, thus furthermore challenging the idea that Bharatanatyam must remain frozen in a curated museum of authenticity. This, in turn, refuses the binaries of East-West or tradition-modernity, thus celebrating the dancers' repositioning as translocal, plural, and a political practice. It causes a change in the lens of observation - as refusal becomes a choreographic method - a powerful act of defiance against inherited norms. This refusal might take many forms: rejecting the use of overly casteist mythologies, refusing to perform in Brahmanical spaces, or declining sringara as a romantic language for male deities. The dancers' transformation from devadasi to symbol of nationalism, after the Western lenses' route to experience the dance form as 'exotic / vulgar,' highlights a larger cultural shift to a symbol of 'high art.' To conclude, as intersectional and political, Bharatanatyam is not a rupture from the past but instead a radical continuity - a remembering and reimagining. It's a practice of healing and resistance, of new reclamation and redefining the norms. As artistes continue to interrogate power through bodies, across space and time, Bharatanatyam becomes more than dance; it becomes a language entitled to liberation. VIVARTA AS PRAXIS In a philosophical context, particularly within the Vedanta system, the doctrine of Vivarta is utilized because it denies a sense of independence to pure chaitanya (consciousness). The initial stage of creation in this view is considered an abhasa, or mere appearance. The journey of space in Bharatanatyam, a classical Indian dance form, is a fascinating blend of tradition and cultural evolution and shifting performance settings. From its roots in temple rituals to modern proscenium stages, the special aspects of Bharatanatyam have constantly evolved, shaping and being shaped by the social and artistic landscapes of each period. FROM TEMPLE COSMOS TO VIRTUAL GRID: HISTORICAL ANCHORING In its earlier forms like Sadir, Bharatanatyam was deeply intertwined with religious and spiritual practices that primarily took place inside the temple grounds. These sorts of performances were often a vital and important part of everyday daily temple rituals carried out by devadasis (temple dancers) right in front of the deity inside the Garbagriha. The space was intimately crafted to foster a spiritual bond between the dancer, the deity, and a small select audience of patrons and devotees. However, with the rise of colonial morality and the anti-nautch campaigns of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this vibrant ecosystem had to face a harsh dismantling. The colonial authority, backed by Indian social reformers, branded devadasi practices as immoral, obscene, and degenerate. As a result, the dance form was pushed to the fringes, and its proactiveness faced significant stigma. CHANGE IN LENS OF OBSERVATIONS The emergence of digital culture has also affected how Bharatanatyam is performed and presented, acting as a driving force in inventing its own social aspects and culturing its aesthetic. While mythological references remain, there is a seen evolution of the portraits that continuously mirror the changing cultural and social landscapes. The gender representation in the dance performances has become much more fluid; where women once depicted male deities like Lord Krishna or Lord Vishnu, today's male dancers are now taking on such roles as acid attack survivors and Goddess Kali. This cultural and phenomenal shift challenges the traditional and general rules and further questions the dynamic historical link between Bharatanatyam and the Devadasi system. Although the historical connection between Bharatanatyam and South Indian temple architecture has faded since the 18th century, the space for performers is an important, yet reimagined hub for symbolic reintegration and cultural expression. Although the refusal doesn't mean absence, it signifies a presence defined by different terms. It opens up room for new stories, diverse aesthetics, and varied bodies. It might mean interrupting the flow of a jatiswaram to insert spoken word protest or juxtaposing adavus with gestures of grief and rage. Thus, this is not just a breaking down of singular dance forms - they are the breakthroughs of meanings. This approach to refuse resonance is what scholar Saidiya Hartman refers to as "critical fabulation": a way of reimagining the histories that have been erased or overlooked through creative and speculative methods. In this context of Bharatanatyam, refusal might manifest as pushing back against the already existing patriarchal gaze, rejecting the underlying casteist narratives, and resistance in the expectation of spiritual transcendence. Such refusal is deeply generative in nature. It opens up new aesthetic terrains and political alliances. Then it shifts the question from "Is this still Bharatanatyam?" to "Who then gets to decide what Bharatanatyam is and what it becomes?" AESTHETICS OF CHANGE IN ATMOSPHERE Atmospheres that can be shared and collectively fabricated are conjured to specific feelings that help to connect bodies within each other to their already existing elemental circumstances. This is a capacity to generate a shared atmosphere and the common space, which suggests an "interstitial (internal) politics." This is effective politics that is shaped out through communal experiences. The rise of digital culture has, in part, transformed artistes, pushing them to reach out to learn how they represent their work in order to connect with the broader audience. Nowadays, you can find everyday dance classes taking place in urban studios, schools, and post-Covid, even online, highlighting a shift in both accessibility and its essential purpose. While the essence of bhakti (devotion) exists and remains, it is often showcased at cultural festivals, competitions, or social awareness events. Take, for instance, the dance videos on Instagram or YouTube, where people are now crafting short Bharatanatyam pieces set to spoken word or poetry or even protest music. Tackling important issues like domestic violence, environmental challenges, and gender identity has made such platforms a representation of how big an art form can be. Multimedia devices like laptops, tablets, smartphones, personal computers, digital cameras, tripods, video projectors, multiple software applications, social media, and more are now used to host live performances directly via several interactive platforms. These innovations reflect a significant change in dance practice, moving from rigid rituals to a more fluid conversation, all while staying rooted in the rich tapestry of Indian mythology, culture, and emotional expression.  The atmosphere of Bharatanatyam has shifted from ritualistic to reformist and from nationalistic to global and intersectional, but its true essence - an expressive and sacred art of storytelling through rhythm and gesture - remains a constant pulse through time. INCORPORATING FUSIONS AND POLITICAL BHARATANATYAM Political Bharatanatyam refuses to isolate art from activism. The choreography of the Shaheen Bagh protest, farmer suicides, and RG Kar protests transforms the stage into a quiet yet sharp rhythm of dissent. Here, mudras become the science of protest, adavus map out journeys of exile and resilience, and abhinaya tell stories that mainstream media neglects. Crucially, intersectional fusion is not just about mixing, matching, and blending styles - it's about acknowledging and honouring the histories and struggles that shape those styles. When the Dalit stories are told through Bharatanatyam, they challenge its casteist gatekeeping. When a trans dancer reclaims space on the stage, it drops certain codifications. When diaspora dancers bring in jazz or hip-hop elements, they question the cultural essentialism of "authentic" Indian identity. THE MATTER OF INTERSECTIONALITY HERE After the centrifugation through 'Sanskritization,' reclamation of sanitizing and recontextualizing dance with an upper-caste, heteronormative, and often patriarchal framework has evolved over time, thus canonizing the mass through multiplicity of bodies, voices, and politics embedded in its origin. However, a new generation of dancers, particularly from the Dalit, queer, diasporic, feminist, and transnational contexts, is reshaping the form. These artistes not only criticize structural injustices but also reclaim Bharatanatyam as the medium for embodied resistance. DECOLONIZING BHARATANATYAM The politics of Bharatanatyam has also become entangled with postcolonial anxieties. Who owns the dance? Whose stories are they telling? Who gets to innovate? Intersectional fusions colonize not just movement vocabularies but also the epistemologies that undergird classical arts, thus dismantling the binaries. As a result, the question is not merely rhetorical - it's urgent and unresolved. The ownership here does not imply who performs the art, but it evaluates the allowances that one has to innovate the structure within it. Who has the right to reinterpret mythology? To infuse new stories, hybrid vocabularies, and resistance aesthetics? When a queer artiste introduces drag aesthetics into a 'Varnam' and a Dalit dancer performs repertoire long terminated by Brahmanical narratives, it often meets with a pushback - which is thinly veiled under the name of tradition but rooted in a deeper class-raising caste anxiety, as it doesn't barrier cultural control. A choreography that speaks of caste oppression or clear joy is no less 'authentic' than one evoking Krishna or Shiva. The concept of what is sacred here is not confined to temples or scriptures - it resides in the act of truth telling, in the courage to dissent, and in the body that refuses 'erasure.' As in the process of healing, we claim resistances, questioning power supervises the ethereal sanctum of Dance, Self, Time and Space. CITATIONS

Brinda Dhar is a sociology student at Presidency University, Kolkata, and a passionate Bharatanatyam dancer. Her interests lie at the intersection of social psychology and dance, aiming to deepen understanding of the human experience through her academic and artistic pursuits. Response * Bharatanatyam - a classical art form - who can own it? Bharatanatyam is a classical art form. Though structured, if one agrees to the codification of Bharatanatyam by Tanjavur Quartet (margam), it has a very dynamic quality allowing to journey through space, time and content. It has a unique stylization which suits all types of genders. The form projects the strength of the stone temples and grace of the creepers within it. If mythology, which forms the backbone of content in Bharatanatyam, is given a historical status; then Bharatanatyam, has the capacity to showcase historical to contemporary events, persons, ideas and views and liberating minds. Thus it is seen that Bharatanatyam has been and is evolving with the times- from temple to proscenium to digital times, holding itself high and already traversed through many challenges, innovations, fusions and fads. Art is that which is beautiful, there is joy in beauty. Conceding that beauty lies in the eye of the beholder, it is rasa as explained by Bharata in “Natyasastra” that helps connect audience to the art form and ideas being showcased. Any art form showcases the feelings and emotions of people living in timeline of the stories presented, by which one learns traditions and culture of those people and their progression through life. Bharatanatyam or any other art form is owned by one who can use it well as a language to express their ideas and concepts and those who receive these sentiments portrayed with joy. - Chandra Anand (July 23, 2025) Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |