|   |

|   |

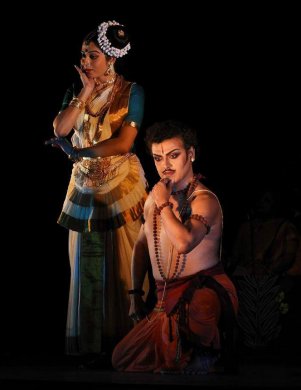

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com Tagore, the early women's libber Photos courtesy: Kalamandalam Calcutta November 26, 2017 Chitrangada, a major verse-play penned by Tagore in 1892, had the eponymous character and all her cohorts taken from the epic Mahabharata. Its narrative had begun on the note of an abject offer of surrender of the protagonist's womanhood at the altar of a macho man: to be his companion, charioteer, follower in hunting, his night guard, devotee, servant and subject. Over four decades later, when Chitrangada was turned by the poet into a dance-drama, he catapulted the image of the Manipuri princess to almost a transcendental level. In the 1936 adaptation, when the world had already seen the rise of the ugly Nazi machismo in the West, Tagore made her utter - - with all the emphasis at her command – the prophetic feminist words: "I am Chitra. I'm no goddess to be worshipped, nor the object of conjugal pity to be brushed aside like a moth with indifference. If you deign to keep me by your side in the trail of danger and daring, if you allow me to share the real duties of your life, you will then know my true worth..." This was the triumphant voice of universal femininity: not satisfied at her gender's essential dignity, but assertive enough to insist on a level of equality, howsoever arduous. Indeed, Tagore was very particular about the stentorian proclamation by the princess in the finale: "I'm Chitrangada, the daughter of 'the king of kings'. I'm neither a goddess nor an ordinary female..." This marked the triumph of an empowered soul, at ease with her existence.  Malabika Sen as Kurupa, Kaushik Chakraborty as

Arjun

The dance-drama Chitrangada, mounted recently by Kalamandalam of Kolkata - - under the batons of Guru Thankamani Kutty and music arranged by the veteran Anita Pal - - unfolded beautifully this liberation as a gradual process. The 'tomboy' princess, reared up emphatically after a son's image by her doting father, romps around for a hunt with her equally boyish companions who disturb a sleeping Arjuna. The latter contemptuously rejects them as a bunch of 'playful boys'. Malabika Sen as Chitrangada, had all the attributes of an excellent dancer, complete with dignified abhinaya, but seemed to be erroneously attired in female costume, as was the case with her mates dressed as feminine dancers. This oversight needs to be corrected in future presentations. At the second stage, the 'woman' within her wakes up and the mental turmoil is like a tsunami: Let the storms come / with the rains heralding new greens winsome... Despite stern warnings of her companions, the awakened princess is keen on listening to the call of her destiny: All the time in mind sublime, I hear / fathomless water's call... She seeks divine grace to acquire alluring beauty, granted through sonorous singing of Madana in Saikat Bandyopadhyay's voice. It is a new birth of Chitrangada: Through all my limbs, who plays the flute? / In joy'n'grief, mind's stoic, absolute... As the bedecked Chitrangada, Mohul Mukherjee has a very mobile and sensitive face, but how does a Mohiniattam costume fit in her Bharatanatyam stances?  Malabika Sen  Mohul Mukherjee as Surupa, Kaushik Chakraborty as Arjun Then comes the delirium of passion and union. Under competent narration by Subir Mitra and great singing by Mrinalkanti Choudhury, Arjuna is elated: Come do come, whoever you are / Do tell me, you're no dream, illusion either... Kaushik Chakraborty as Arjuna is an old hand on Kolkata stage with his long grooming in Kathakali, but he should beware lest his hastamudras (hand gestures) become a little jaded and stereotyped. The fourth stage is a harbinger of disillusion and a last desperate fling at re-kindling the lost amour with a pas de deux: Time went past on separation's mast in plucking visionary dream / All roads at last have met in repast in your two eyes' ream... Mohul also needs to watch out on her occasional awkward pauses. The fifth and last stage is that of dual awakening: of Arjuna, from the stupor of monotony in carnal love and of Chitrangada, from the cardinal mistake of confusing between physique and psyche. In a superb final gesture, she throws away her sham garb of the enchantress and reveals her real, radiant self of a power-house. Kalamandalam also should pull up its support system. Lighting was pretty erratic, quite often missing the target zone. Microphones for the choral singing were poorly coordinated, quite often enfeebled and inaudible, as distinct from the clarity of the solo mikes. Choral singing seemed to need more rehearsals, as did group dances of the companions and, later, villagers. These were, however, minor blemishes in an overall brave effort on a theme very relevant today.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Comments * Thanks to Narthaki and Dr. Utpal Banerjee for your valuable comments. Although, we do not agree with all your observations, however, we will surely delve into the points raised by you and look into the necessary corrections for our future presentations. - Somnath G.Kutty, Secretary,Kalamandalam Calcutta(Nov 27, 2017) Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |