|

|

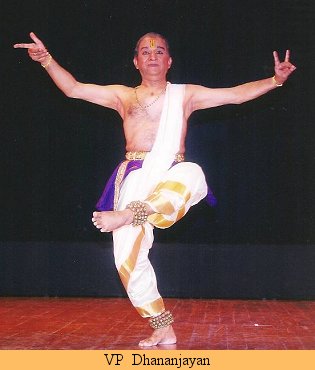

The dramatics

of the Dhananjayans

December 8, 2009

Nritya Tarangani followed with the singing of "Sankara Srigiri" of Swati Tirunal in Hamsanandi. It was a tribute to Lord Nataraja providing opportunities for showing many of his poses with a dramatic finale complete with the subjugation of Muyalakan. The piece-de-resistance was the episode involving Manthara, Kaikeyi and Dasaratha from Ramayana when the die was cast for crowning Bharata and sending Rama to the forest. It was a masterpiece in angikabhinaya, or the language of mime, as the Westerner would call it. Although there was singing, considerable sections were done in absolute silence with the actors doing their conversation - pleading, rebutting, arguing - through the language of hasta mudras and body movements. Since the story was well known, there was no problem for the spectators to understand and appreciate what was happening on the stage. Shanta (Manthara), Dhananjayan (Dasaratha) and Divya Shivasundar (Kaikeyi) were superb in their roles. What is more, there were meaningful pauses bringing out their importance in tense moments in life. There was an appropriate mix of lokadharmi and natyadharmi in the enactment without any overkill of either. Ramayana was followed by the story of Bhagavatam with the song "En palli kondir ayya" (Mohanam) of Arunachala Kavi as the prefix followed by Bhajamana of Tulsidas. Dhananjayan's mukhajabhinaya in this as well as the earlier one in respect of such emotions as adbhuta was an object lesson for students in the audience on the process of the transformation of bhava into rasa. The programme finished with Nritta Angahara, a garland of nritta movements, which the artistes offered to the audience. It had a tillana of Balamurali (1968) as the base. Though long, the kaleidoscopic patterns woven with seven dancers were such as to grip the attention of viewers. The audience must have felt happy with a Sunday evening well spent as the entire team of dancers and the supporting orchestra exhibited high standards associated with Bharata Kalanjali with more than four decades of experience in the field. Sakti Prabhavam and Bhakti Pravaham

Nandanar

In the early years of the 20th century there was in the USA, a theatre movement for realism in the portrayal of characters. It was started by Constantin Stanislavski (1863-1938), a well-known Russian actor, director and producer. It was called "The Stanislavsky Method" or simply "The Method." He said: "…. let us learn once and for all that the word 'action' is not the same as 'miming'; it is not anything the actor is pretending to present, not something external, but rather something internal, non-physical, a spiritual activity... There is only one thing that can lure our creative will and draw it to us and that is an attractive aim, a creative objective… The best creative objective is the unconscious one which, immediately, emotionally, takes possession of an actor's feelings, and carries him intuitively along to the basic goal of the play. The power of this type of objective lies in its immediacy (the Hindus call such objectives the highest kind of superconsciousness), which acts as a magnet to creative will and arouses irresistible aspirations" (Twentieth Century Theatre - A Source Book, Edited by Richard Drain). Basically the technique requires the actor to live his part in order to be realistic. He is asked to look into himself to find the basis for emoting on the stage - a process of internalisation. To produce the maximum impact on the spectators, they should be made to believe that the actor really feels the emotions he is displaying. Although all this appears to be commonplace now, it was revolutionary at the time Stanislavsky said it because the prevailing idea in USA then was that actors and actresses should mimic characters in a play effectively to be successful. Stanislavsky had great following among Directors like Elia Kazan, Robert Louis and Lee Strasberg. The Actors Studio in New York, founded in 1947 by Kazan and his colleagues and headed by Strasberg from 1948 to 1982, produced such eminent actors as Marlon Brando, James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Marilyn Monroe and Robert DeNiro. The Method gained popularity especially after Brandon's memorable performance in the film A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by Kazan, which won many awards. Another equally powerful movement inspired by Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), German dramatist and theatre director, espoused a different idea. His purpose was "to persuade the audience to forego the usual theatrical pleasure of empathy with the protagonists; and to enjoy instead an all-round view of them, seeing their interaction from new angles and relishing ironies. In this way, the audience is enlisted as engaged critical observer rather than as the object of emotional or spectacular bombardment…. The message implicit in it for his audience is the message he gave his actors: don't get carried away." (Ibid.) Two keys to the technique are the notion of "theatricalism" and the concept of the "distancing" or "alienation" effect. The first, theatricalism, simply means members of the audience being made aware that they are in a theatre watching a play. Brecht believed that seducing the audience into believing they were watching "real life" led to an uncritical acceptance of society's values. He was a Marxist with leftist leanings and wanted to reform society through theatre, exposing the iniquities of the time in terms of social injustice. The second key to his theatre was the "distancing" or "alienation" effect in acting style with the same goal as the first one. He wanted actors to strike a balance between "being" their character onstage and "showing the audience that the character is being performed." The Method

in Indian Dance

The mukhajabhinaya and body language of Dhananjayan carried a strong accent of Kathakali. It was natural given the fact that he has had formal training in Kathakali besides in Bharatanatyam. He being a Keralite, it is second nature to him. There is nothing wrong about it as it was seamless and merged beautifully with the rest of the Bharatanatyam format. Seeing Nandanar, one saw the importance of the study of body language, or, Kinesics, as it is called in the West, which was pioneered by Rudolf von Laban, the Hungarian choreographer and dance teacher, in 1926. Long before Laban, one of the schools of Kathakali, viz., Kalluvazhi Chitta, emphasised the elements of cuzhippu - the coordinated movements of hands, eyes and body by which the entire structure of dance became more beautiful. Rukmini Devi had an eclectic approach to music and dance and had an in-house Kathakali master at Kalakshetra, of which the Dhananjayans are the alumni. For example, she introduced Kalaripayattu, a martial art of Kerala, in Meenakshi Kalyanam at a time when no one talked about fusion in Indian classical dance. The story of Nandanar, enacted by Dhananjayan, with emphasis on gestural language had a strong Kathakali touch. An authoritative text on Kathakali says: "While the dialogue is being rendered by the vocalist singing the text, the actor interprets each word through hand gestures, body movement and facial expressions. The vocalist repeats the line for completing the hand gestures. There are dialogues without vocal music between the characters. In some scenes, there is only angikabhinaya or body movement without vocal support for hours, in a traditional performance. Here the actor has ample scope to lend wings to his imagination and elaborate the text." (Kathakali, S Balakrishnan, Wisdom Tree). In fact, as a long-standing rasika, and not as a choreologist, I would like to define the Kalakshetra style as follows. Pandanallur style + Elements of Kerala dances - erotic rati sringara of Sadir = Kalakshetra style This is, of course, debatable. The drama ended with "Kanakasabhai tiru natanam" in Surati probably because it is a mangala or auspicious raga appropriate for rounding off a concert. However, I would have loved to see and hear the Abhogi kriti "Sabhapatikku veru deivam samanamakuma?" ("Is there any other god equal to Sabhapati?"). In the charanam of this song by Gopalakrishna Bharati, there is a reference to "Ariya pulaiyar moovar" ("The rare threesome of pulaiyars or dalits"). According to U V Swaminatha Iyer's biography of Bharati, the threesome are Tillaivettiyan, Petran Sambhan and Nandan Sambhan - or Nandanar (Sangeeta Mummanikal, Mahamahopadhyaya U V Swaminatha Iyer Library). Abhogi is preferred by musicians to be sung early in their concerts to impart tempo, not at the end, but there are always exceptions to rules. There is a story associated with the kriti under reference. When Bharati visited Tyagaraja, his disciples were singing his Abhogi composition "Sri Ramaseeta alankara swarupa." Tyagaraja asked the visitor whether he had composed any kriti in that raga. Bharati said "no." Overnight he composed "Sabhapatikku" and sang it before him on the next day. Tyagaraja appreciated his musical acumen. (Ibid.) Thanks to him, we know about Nandanar. But there is little known about the other two Siva bhaktas. Gopu Kiran was the ideal choice for the role of the Brahmin (Vediyar). He looked and essayed his part very well with his costume, demeanour and haughty looks and behaviour towards Nandanar. M Venkatakrishnan wowed the audience with his sculpture-like stance without any movement or tremors in his body for quite some time when he played the role of the Nataraja idol in one of his nartana poses during the song "Vazhi maraittirukkude." It was an endurance test that he passed with distinction! As on the previous day, the orchestral support contributed greatly to the effectiveness of the programme. Shanta Dhananjayan wielded the cymbals with élan. Dhananjayan was gracious enough to mention the good support received from, among others, Raghu, the in-house tambura vidwan and staff member of the Sabha. The two-day programme of Bharata Kalanjali was yet another illustration of the success of synergy - the total effect being more than the sum of the individual ones due to excellent teamwork. Dhananjayan, a septuagenarian, and his wife are in trim shape physically and are role models for youngsters. One wishes them many more years of outstanding contributions to the world of art and culture. The author, an Economic Consultant in Mumbai, is a music and dance buff. |