|

|

A Dance Tribute to Ravi Varma by A Seshan, Mumbai e-mail: aseshan@bol.net.in February 21, 2003 |

|

|

|

|

| Kanaka

Sabha, the institution devoted to the propagation of Bharatanatyam and

Kuchipudi in Mumbai, presented an innovative and interesting programme

at the auditorium of the National Gallery of Modern Art in the Fort area

in Mumbai on February 12, 2003. It was in conjunction with the exhibition

of the paintings of Raja Ravi Varma as part of the multifarious events

in The Kalaghoda Art Festival.

The Kala

Ghoda Art Festival

To mobilise their support for the worthy cause of preserving the arts of India and the heritage buildings in the locality and with a view to making it the Art District of the city, The Kala Ghoda Association was formed in October 1998 by a group of civic-minded volunteers many of whom are prominent individuals known for their contribution to enriching the quality of life in the city. Its Chairman is S.A. Sabavala. The Art Festival is one of the major activities of the Association undertaken every year with the help of Government of India and many individuals and institutions. The nine-day festival, with participation by both Indian and foreign artistes, was held this year during February 8-16, 2003. It sought

(i) to raise public awareness in terms of establishing an identity for

the Art District,

A beautiful pamphlet brought out by the Association lists a number of mind-boggling varieties of events – exhibitions (both indoor and outdoor), workshops films, fashion, food, merchandise, street theatre, readings, seminars, lectures, demonstrations, debates, music, dance, heritage walk, etc. This writer counted nearly 140 events packed in a period of nine days all held within a square kilometre! The Festival scores over the December Music and Dance Season in Chennai in terms of the scope and varieties of activities. Exhibition

of Raja Ravi Varma’s Paintings

It is the first time that the paintings have been moved out of the palace in Baroda. The royal family has 41 collections of the painter but only 31 were selected for the exhibition because of the risk involved in moving them to Mumbai given their delicate state. Each painting was packed with extreme care and brought to Mumbai by couriers after they were insured for crores of rupees. Some works and frames were reported to weigh 200 kgs! Dr Saryu Doshi, a well-known industrialist and patron of arts, should be given the credit for persuading the Baroda prince to agree to the idea. Ravi Varma, a self-trained artist, was the first Indian to follow the European conventions and techniques by painting with oils on canvas. His name and fame spread outside the shores of India and many exhibitions were held of his paintings abroad and prizes won. He was given the title of Kaiser-I-Hind by the British Government. Impressed by his artistic skills a number of members of the British elite and Indian royalty commissioned him to do their portraits. But, more than his portraits of personalities, it is his drawings of episodes from Hindu mythology, which have left an imprint on the art world. One always remembers his pictures of Viswamitra turning his back on Menaka, the fight between Ravana and Jatayu, Damayanti writing a message to Nala, and so on. The Dance

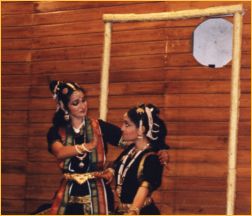

But here the scope was much more. The presentation, which lasted only an hour, was divided into three parts, viz., Shilpa Kavya (based on Belur sculptures), Drishya Kavya or Chitra Kavya (based on the paintings) and Laya Kavya (based on rhythm). Siri Rama, the well-known choreographer now based in Singapore, also participated in the dance. The others were Juhi Ramakrishnan, Rumya Ramanathan, Sarikha Shetty, Shobitha Ravi, Sujaya Kotian and Vidhya Mani - stars of Kanaka Sabha, who have taken part in many dance dramas of the institution in India and abroad and earned the appreciation of rasikas. They were particularly happy on this occasion because their guru joined them after many months. The latter had been out of action for quite some time due to some physical discomfort. Their performance was so uniformly good that it would be invidious to single out a few dancers for comments. Some general remarks would be more appropriate. Shilpa Kavya: The sculptures of the Chennakesava temple in Belur were the theme of the first item. The song “Sri Chennakesava” in Charukesi in Adi tala set the stage for entering the world of sculptures. The bracketed figures of the temple portray beautiful maidens and different seasons and moods. They have inspired songs and poetry over centuries. Chennakesava, a form of Vishnu, brought the world alive with different moods like anger, laughter, surprise, etc. “Vasantika”, a song in Mohanakalyani and Adi tala, referred to a maiden’s celebration of the beginning of spring. She brings joy and colour to everyone around. The question is asked: Is she spring itself or the female who is an eternal joy in everyday life? (Many men may question this question!) The next item was “Nishade” in Malhar and Tisra Eka. It reminded the audience that the woman of today and yesterday was once upon a time a huntress along with man. (Husbands would say that she continues to be a huntress even today, the catch being their money!) She was a woman who had confidence in herself, could play with nature and could strike down men, not with arms, but with so little as a glance. It revealed an inner strength, which challenged even the divine (Shades of feminism!). “Mohini” in Mohana raga and Rupakam was a tribute to the beauty of woman, which could lure even the demons to their disaster and deliver nectar to the gods. She could mesmerise even Lord Shiva. Drishya Kavya: Raja Ravi Varma was much inspired by the Marathi theatre, its key characters and plots. They provided an inspiration to him. A famous song from Marathi stage (“Jai Ganga Bhagirathi)” provided the background to the next dance. The river was portrayed as one that inspired life and death, the divine and the mundane. There was a representation of modern India also. Mythological characters were favourites with the painter. His work on one of the episodes from the Ramayana, viz., Jatayu Moksham, has been popular with his admirers. Taken from Tulsidas Ramayana, the dance portrayed the episode as the eternal battle between the good and the evil which the world finds itself locked in from time to time. It was a recitation set to misra nadai. The eternal lovers, Krishna and Radha, who defied conventional rules and norms of society, provided the inspiration for one of the paintings. A Meera bhajan in Yaman Kalyan and Misra Chapu described the spring season and the two lovers enjoying each other’s company in a swing in the garden. The Marathi stage inspired yet another piece in the oeuvre. Set in Misra Pilu and Tritaal the episode refers to the desertion of Shakuntala by King Dushyant. She is worried about her future and notes that she is sad at a time when she should be happy. Laya Kavya: It was a demonstration of nritta to show how rhythm could also produce images. It was an abstract piece in pure dance inspired by a contemporary rhythmic ensemble. It found joy amidst the problems of the fragmented world of today. One observation on the whole production is that it was fast- paced keeping in mind the limited time and the vast canvas to be covered. There was thus not a dull moment, not even a short interval between scenes. The first song was exploited to display satvikabhinaya. The dancers brought out the navarasas in turn in a quicksilver fashion. The sculptural poses were well executed. Incidentally, the choreographer had received a doctorate from the University of Hong Kong for her thesis on the dance sculptures of Belur and Halebid and was therefore quite familiar with them. In this segment of the programme one remembers such figures as a surasundari applying tilak to her forehead looking at a mirror in hand, which is a perennial favourite with photographers of Belur temple, the dance of the temptress Mohini and the primordial huntress who hunted animals with bow and arrow but could subdue men with just her looks. Shilpa Kavya had an interesting end when all the dancers recited the jatis together in a vibrant manner sending the audience to foot tapping. Drishya Kavya was evocative of the paintings. The fight between Jatayu and Ravana, Shakuntala’s sorrow and the joyful dalliance of Radha and Krishna were well done. And when the dancers stepped out of the large frame on the stage it looked like the paintings had come alive! They identified themselves completely with the characters they played. Laya Kavya was marked by vigorous footwork providing a rousing finale. This writer has only a couple of critical comments of a technical nature. They do not in any way detract from the excellent impression left on the audience as could be gathered from the viewers after the programme. Generally, in a group dance, there are occasions when all the dancers have the same leg and hand movements depicting a common idea or pose. One aspect that caught the attention of this writer was that in such cases some times the hands of the artistes were not synchronised or coordinated. In other words, say, when the hands had to be raised by all over their heads, at any point of time or place in the song, their positions were at different levels for different dancers while they were in the process of reaching the final one. Now this is nothing unusual. This writer has seen this happening in a number of group dances choreographed by other equally professional and reputed natyacharyas. It is, course, no excuse. There is no doubt an inherent difficulty because when all the artistes face the audience they cannot see each other’s movements. But still one wonders whether it is not possible to achieve synchronisation and coordination if the movement is firmly anchored, as it should be, to music as the benchmark. Thus, at any point in music, there should be a common hand or leg or foot position. The hand positions (hastakshetra, one of the lakshanas of anga suddha) are more easily seen than those of the feet and hence invite comments! One should not dismiss this observation as nit-picking. Professionalism is all about nuts and bolts. The audience was surprised by the aharya. While make-up was well done transforming the girls literally into the characters they represented, it was somewhat overwhelming when they entered the stage in shimmering black. Since the programme was only for an hour there was no time to change clothes in between. This writer enquired of the choreographer as to why she chose black over other colours for the costumes. She said that since sculptures were to be portrayed she thought it appropriate to have the dress in a colour close to the greyish black of the stones. Also, uniformity in the dresses of all the dancers highlighted a certain symmetry. The rationale is convincing. Still this writer felt that the occasion was a celebration of art and culture, indeed of life itself. Paintings were also represented besides sculptures. Would it not have been more impressive if the colours had been, say, red or green? Better still, a melange of colours among the dancers would have brought out the generous application of paints and brilliant chiaroscuro effects for which the artiste’s works are known. Of course, black is beautiful! There was recorded music. It was good there was no live orchestra because there was just no space for it on the small crescent-shaped stage! The accompanying artistes were Usha Srinivasan (Carnatic vocal), Jyoti Bhatt (Hindustani vocal), Ravi (Violin), Lalitakalalayam Nambisan (Mridangam), Narayan Mani (Veenai) and Deepak Chowdhury (Flute). Being experienced professionals and veterans in their fields they all displayed their usual high standards. But the Meera Bhajan was somewhat hurried and could have been at a slower tempo. Perhaps the speed of the swing, referred to in the song (“Jhoolatha Radha”), influenced the singer! One important

reason for the rapport established between the artistes and the audience

was the small size of the semi-circular auditorium and the ambience. One

has heard of chamber music. It was chamber dance at its best. There was

accommodation for about 100 persons only. The venue was at the southern

end of the island. The programme was after office hours when it was

time for everyone to proceed to bus stops and railway stations to commute

to the northern suburbs. Thus only the really interested persons could

be expected to attend the programme. The auditorium was overflowing

with some sitting on the small steps near the chairs and others standing.

The stage was small and, in the first item, two of the dancers had to get

down from there on the floor to perform. There was rapt attention thanks

to the close view that the rasikas could have of every nuance of

the dance. To sum up, the programme was yet another feather (or flower)

in the caps of the choreographer and her students.

A Seshan is an Economic Consultant in Mumbai, formerly Officer-in-Charge

of the Department of Economic Analysis and Policy in the Reserve Bank of

India. He is a music and dance enthusiast and writer.

|